How Much is Your Data Worth?

How Much is Your Data Worth?

How Much is Your Data Worth?

How Much is Your Data Worth?

How Much is Your Data Worth?

How much is your data worth? This is a research project that attempts to answer this very question, and expose how much your ad activity could be worth according to Google’s algorithms. It is not an exact calculation of Google’s ad revenue per user, but rather an investigation or inquiry into your role as a digital consumer – and laborer – in the vast landscape of surveillance capitalism and adtech.

In 2019, Google made 162 billion dollars in revenue. The majority of this – amounting to 134.81 billion dollars – was made from its advertising service, Google Ads.

When we use Google's search engine and click on the top results that are labelled as an “Ad”, Google charges businesses an average of $1 to $2 per click. The metric for measuring the valuation of a ‘click’ is referred to a CPC, or a cost-per-click. CPCs can range from over thousand dollars to just a few cents, depending on an auction process that evaluates the ad quality, projected impacts, and other abstract mechanisms made invisible to the user.

In the broad context of adtech, it is important to note that we also pay for the data that is required to load ads. According to a New York Times study, more than half of all data on 50 news websites came from mobile ads. In essence, we pay for the digital labor that we perform.

Branded as a free service, Google Search uses adhesion – or sticky – contractual relationships to capitalize on the unpaid digital work performed by consumers. But this service is far from being free, as consent is a non-negotiable, abstract, and opaque requirement that offers users the space to participate in civil society and social infrastructures, in return for their agency. According to Cheryl B. Preston and Eli McCann, “Cyberspace, instead of being free, open, and liberating, is emerging as a feudal system controlled by contract.” In this post-industrial feudalist relationship, marked by an erosion of the boundaries that once defined the extent and scope of contractual relationships, what becomes of our agency and self-awareness? Are we willing participants in the apparatus of surveillance capitalism?

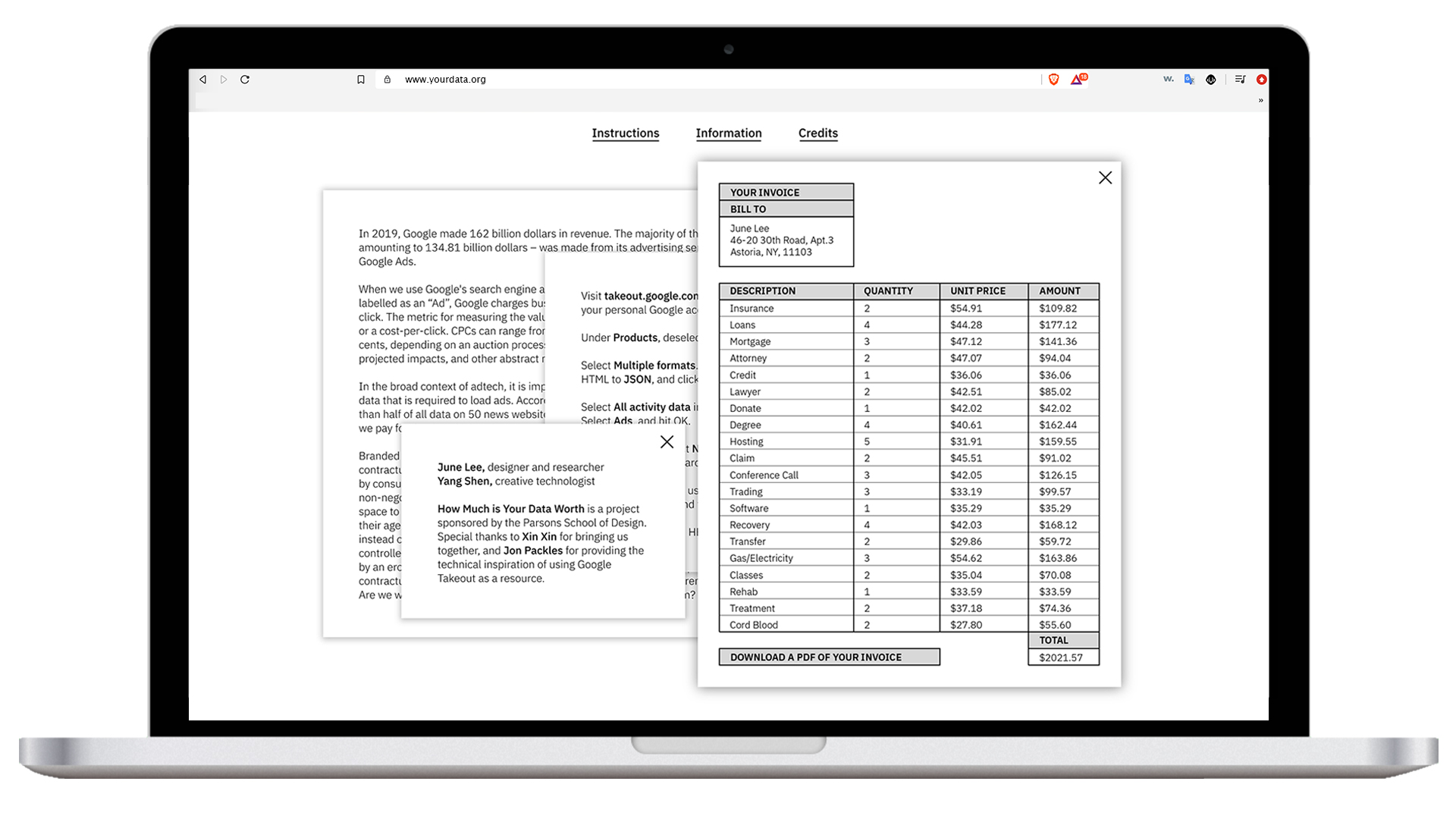

Project team:

June Lee, Designer and Researcher

Yang Shen, Creative Technologist

How Much is My Data Worth is a project sponsored by Parsons School of Design. Special thanks to Xin Xin for bringing us together, and Jon Packles for providing the technical inspiration of using Google Takeout as a resource.

How much is your data worth? This is a research project that attempts to answer this very question, and expose how much your ad activity could be worth according to Google’s algorithms. It is not an exact calculation of Google’s ad revenue per user, but rather an investigation or inquiry into your role as a digital consumer – and laborer – in the vast landscape of surveillance capitalism and adtech.

In 2019, Google made 162 billion dollars in revenue. The majority of this – amounting to 134.81 billion dollars – was made from its advertising service, Google Ads.

When we use Google's search engine and click on the top results that are labelled as an “Ad”, Google charges businesses an average of $1 to $2 per click. The metric for measuring the valuation of a ‘click’ is referred to a CPC, or a cost-per-click. CPCs can range from over thousand dollars to just a few cents, depending on an auction process that evaluates the ad quality, projected impacts, and other abstract mechanisms made invisible to the user.

In the broad context of adtech, it is important to note that we also pay for the data that is required to load ads. According to a New York Times study, more than half of all data on 50 news websites came from mobile ads. In essence, we pay for the digital labor that we perform.

Branded as a free service, Google Search uses adhesion – or sticky – contractual relationships to capitalize on the unpaid digital work performed by consumers. But this service is far from being free, as consent is a non-negotiable, abstract, and opaque requirement that offers users the space to participate in civil society and social infrastructures, in return for their agency. According to Cheryl B. Preston and Eli McCann, “Cyberspace, instead of being free, open, and liberating, is emerging as a feudal system controlled by contract.” In this post-industrial feudalist relationship, marked by an erosion of the boundaries that once defined the extent and scope of contractual relationships, what becomes of our agency and self-awareness? Are we willing participants in the apparatus of surveillance capitalism?

Project team:

June Lee, Designer and Researcher

Yang Shen, Creative Technologist

How Much is My Data Worth is a project sponsored by Parsons School of Design. Special thanks to Xin Xin for bringing us together, and Jon Packles for providing the technical inspiration of using Google Takeout as a resource.

How much is your data worth? This is a research project that attempts to answer this very question, and expose how much your ad activity could be worth according to Google’s algorithms. It is not an exact calculation of Google’s ad revenue per user, but rather an investigation or inquiry into your role as a digital consumer – and laborer – in the vast landscape of surveillance capitalism and adtech.

In 2019, Google made 162 billion dollars in revenue. The majority of this – amounting to 134.81 billion dollars – was made from its advertising service, Google Ads.

When we use Google's search engine and click on the top results that are labelled as an “Ad”, Google charges businesses an average of $1 to $2 per click. The metric for measuring the valuation of a ‘click’ is referred to a CPC, or a cost-per-click. CPCs can range from over thousand dollars to just a few cents, depending on an auction process that evaluates the ad quality, projected impacts, and other abstract mechanisms made invisible to the user.

In the broad context of adtech, it is important to note that we also pay for the data that is required to load ads. According to a New York Times study, more than half of all data on 50 news websites came from mobile ads. In essence, we pay for the digital labor that we perform.

Branded as a free service, Google Search uses adhesion – or sticky – contractual relationships to capitalize on the unpaid digital work performed by consumers. But this service is far from being free, as consent is a non-negotiable, abstract, and opaque requirement that offers users the space to participate in civil society and social infrastructures, in return for their agency. According to Cheryl B. Preston and Eli McCann, “Cyberspace, instead of being free, open, and liberating, is emerging as a feudal system controlled by contract.” In this post-industrial feudalist relationship, marked by an erosion of the boundaries that once defined the extent and scope of contractual relationships, what becomes of our agency and self-awareness? Are we willing participants in the apparatus of surveillance capitalism?

Project team:

June Lee, Designer and Researcher

Yang Shen, Creative Technologist

How Much is My Data Worth is a project sponsored by Parsons School of Design. Special thanks to Xin Xin for bringing us together, and Jon Packles for providing the technical inspiration of using Google Takeout as a resource.

How much is your data worth? This is a research project that attempts to answer this very question, and expose how much your ad activity could be worth according to Google’s algorithms. It is not an exact calculation of Google’s ad revenue per user, but rather an investigation or inquiry into your role as a digital consumer – and laborer – in the vast landscape of surveillance capitalism and adtech.

In 2019, Google made 162 billion dollars in revenue. The majority of this – amounting to 134.81 billion dollars – was made from its advertising service, Google Ads.

When we use Google's search engine and click on the top results that are labelled as an “Ad”, Google charges businesses an average of $1 to $2 per click. The metric for measuring the valuation of a ‘click’ is referred to a CPC, or a cost-per-click. CPCs can range from over thousand dollars to just a few cents, depending on an auction process that evaluates the ad quality, projected impacts, and other abstract mechanisms made invisible to the user.

In the broad context of adtech, it is important to note that we also pay for the data that is required to load ads. According to a New York Times study, more than half of all data on 50 news websites came from mobile ads. In essence, we pay for the digital labor that we perform.

Branded as a free service, Google Search uses adhesion – or sticky – contractual relationships to capitalize on the unpaid digital work performed by consumers. But this service is far from being free, as consent is a non-negotiable, abstract, and opaque requirement that offers users the space to participate in civil society and social infrastructures, in return for their agency. According to Cheryl B. Preston and Eli McCann, “Cyberspace, instead of being free, open, and liberating, is emerging as a feudal system controlled by contract.” In this post-industrial feudalist relationship, marked by an erosion of the boundaries that once defined the extent and scope of contractual relationships, what becomes of our agency and self-awareness? Are we willing participants in the apparatus of surveillance capitalism?

Project team:

June Lee, Designer and Researcher

Yang Shen, Creative Technologist

How Much is My Data Worth is a project sponsored by Parsons School of Design. Special thanks to Xin Xin for bringing us together, and Jon Packles for providing the technical inspiration of using Google Takeout as a resource.

How much is your data worth? This is a research project that attempts to answer this very question, and expose how much your ad activity could be worth according to Google’s algorithms. It is not an exact calculation of Google’s ad revenue per user, but rather an investigation or inquiry into your role as a digital consumer – and laborer – in the vast landscape of surveillance capitalism and adtech.

In 2019, Google made 162 billion dollars in revenue. The majority of this – amounting to 134.81 billion dollars – was made from its advertising service, Google Ads.

When we use Google's search engine and click on the top results that are labelled as an “Ad”, Google charges businesses an average of $1 to $2 per click. The metric for measuring the valuation of a ‘click’ is referred to a CPC, or a cost-per-click. CPCs can range from over thousand dollars to just a few cents, depending on an auction process that evaluates the ad quality, projected impacts, and other abstract mechanisms made invisible to the user.

In the broad context of adtech, it is important to note that we also pay for the data that is required to load ads. According to a New York Times study, more than half of all data on 50 news websites came from mobile ads. In essence, we pay for the digital labor that we perform.

Branded as a free service, Google Search uses adhesion – or sticky – contractual relationships to capitalize on the unpaid digital work performed by consumers. But this service is far from being free, as consent is a non-negotiable, abstract, and opaque requirement that offers users the space to participate in civil society and social infrastructures, in return for their agency. According to Cheryl B. Preston and Eli McCann, “Cyberspace, instead of being free, open, and liberating, is emerging as a feudal system controlled by contract.” In this post-industrial feudalist relationship, marked by an erosion of the boundaries that once defined the extent and scope of contractual relationships, what becomes of our agency and self-awareness? Are we willing participants in the apparatus of surveillance capitalism?

Project team:

June Lee, Designer and Researcher

Yang Shen, Creative Technologist

How Much is My Data Worth is a project sponsored by Parsons School of Design. Special thanks to Xin Xin for bringing us together, and Jon Packles for providing the technical inspiration of using Google Takeout as a resource.

Our methodology began with an objective to create transparency in the web. We researched topics and prototyped ideas that relate to browser infrastructure, an exploration of the internet as a form of time-based media, non-western design philosophies and aesthetics, the meaning of consent in digital technologies, and the complexities of digital marketing schemes and adtech. We kept a Google Doc of our research notes and findings, and held bi-weekly meetings to review our progress. In one of our meetings, we decided to focus on adtech and the issue of consent because they are so opaque to the everyday user.

Here are the main issues with adhesion contracts which pervade today's digital platforms:

- There is a lack of ample notice and a clear consent to contract;

- Digital platforms enable unlimited availability of space that permits very long and complex terms

- Contracts have extreme provisions and waiver, purposely inserted with the knowledge that users will not read them

- Embedded in digital platforms, they are used in a context marked with speed and instant gratification

Here are some common elements found in contracts that are harmful to the everyday user:

- Unilateral modification clauses which permit the creator of the contract to change or add items without notice

- Jury waiver

- Venue restrictions

- Arbitration clauses

- Transfer of intellectual property rights: Eg. In the FB user agreement, users grant “a non-exclusive, transferable, sub-licensable, royalty-free, worldwide license to use any IP content that you post on or in connection with Facebook.”

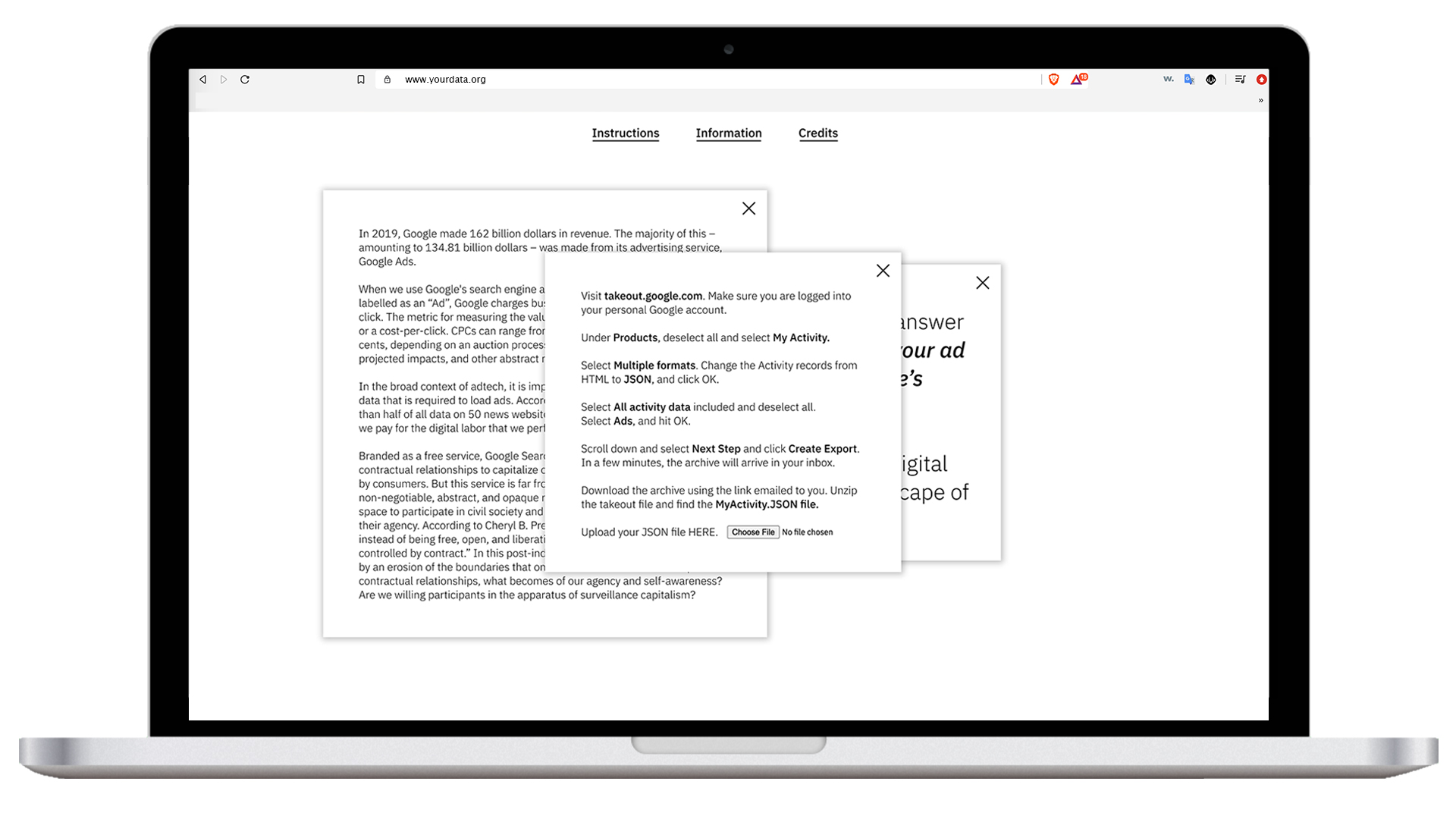

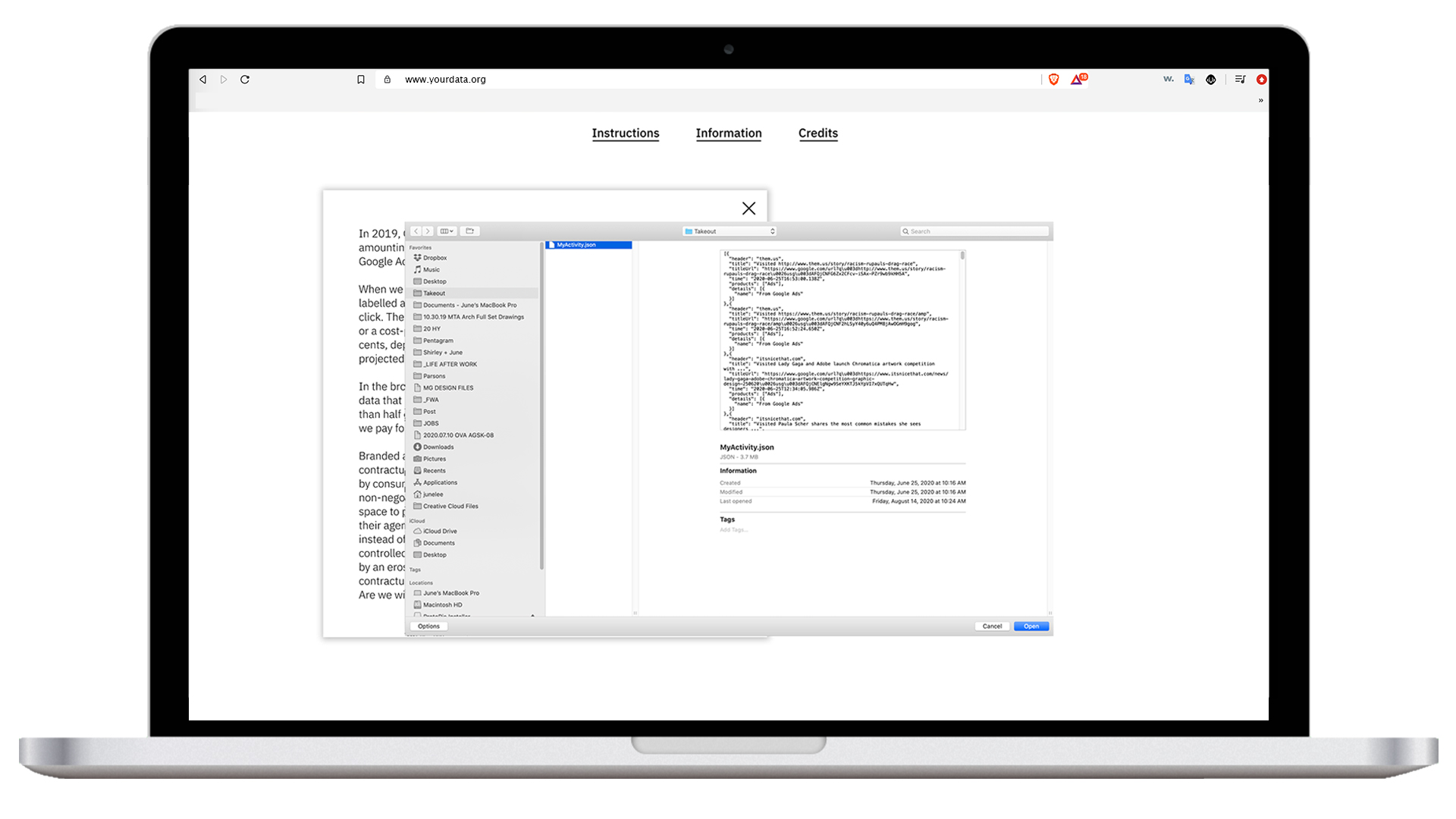

From these findings, we created a series of questions to ask ourselves to inform what we are responding to and how. One of the questions we raised was, “how much is our data worth?” As we confronted this seemingly impossible question, we also found it to be easier to estimate than we initially expected. We encountered hundreds of resources online that allows businesses to estimate the CPC of virtually any keyword imaginable. Jon Packles’ Search Record, a poetic interpretation of user data on Google Takeout, provided the technical means to finally reach our goal of estimating just how much our data is worth.

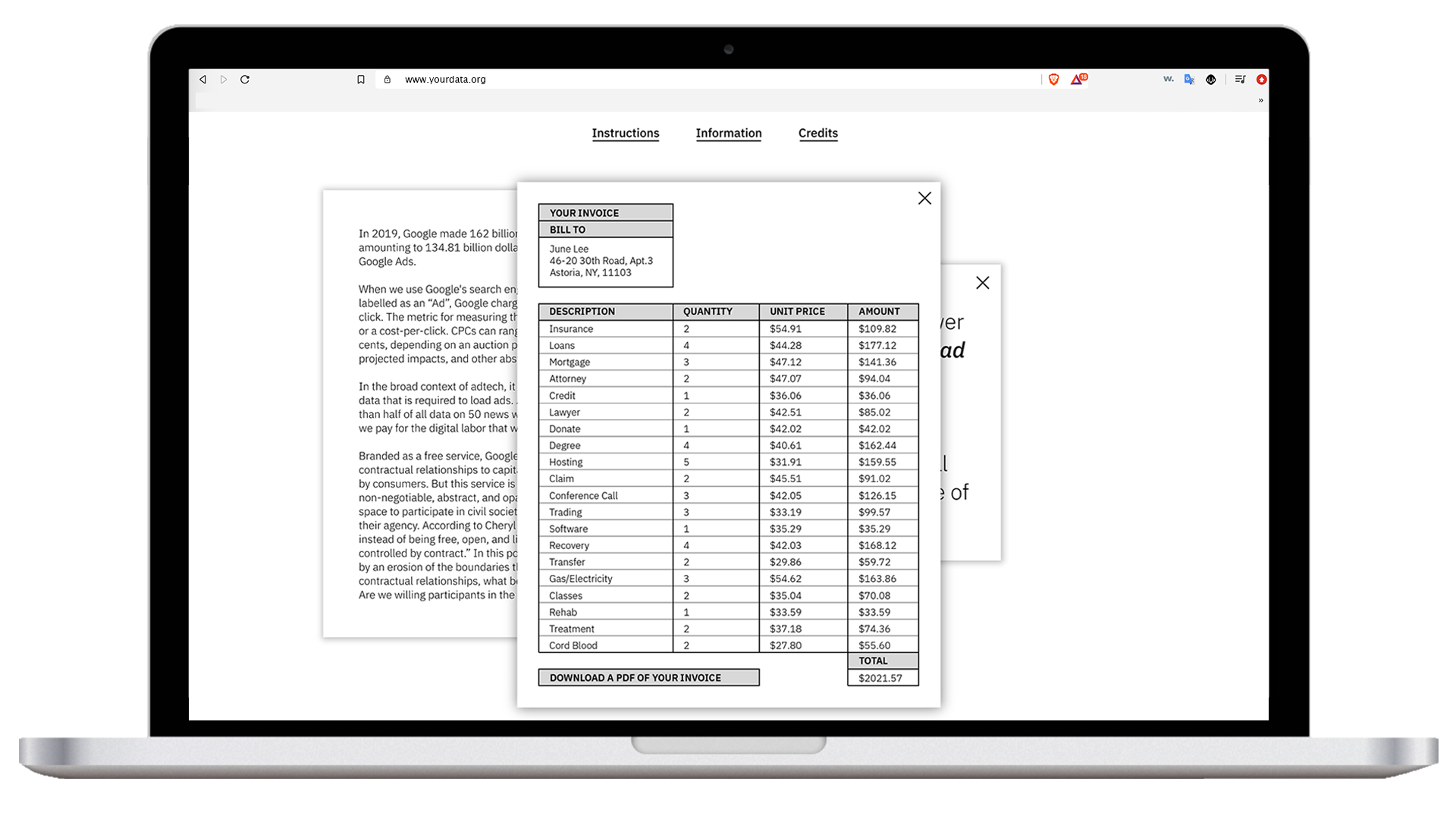

This project currently analyzes a limited number of keywords, and isn’t calculating every single keyword you have typed into Google search. On our list, the most expensive keyword is “insurance” ($54.91 USD per click) and the least expensive keyword is “pandemic” ($0.10 USD per click). You can find our expanding list of keywords here.

Resource:

Cheryl B.Preston and Eli McCann, “llewellyn Slept Here: A Short History of Sticky Contracts and Feudalism,” Oregon Law Review Vol. 91, No. 1 (2012).

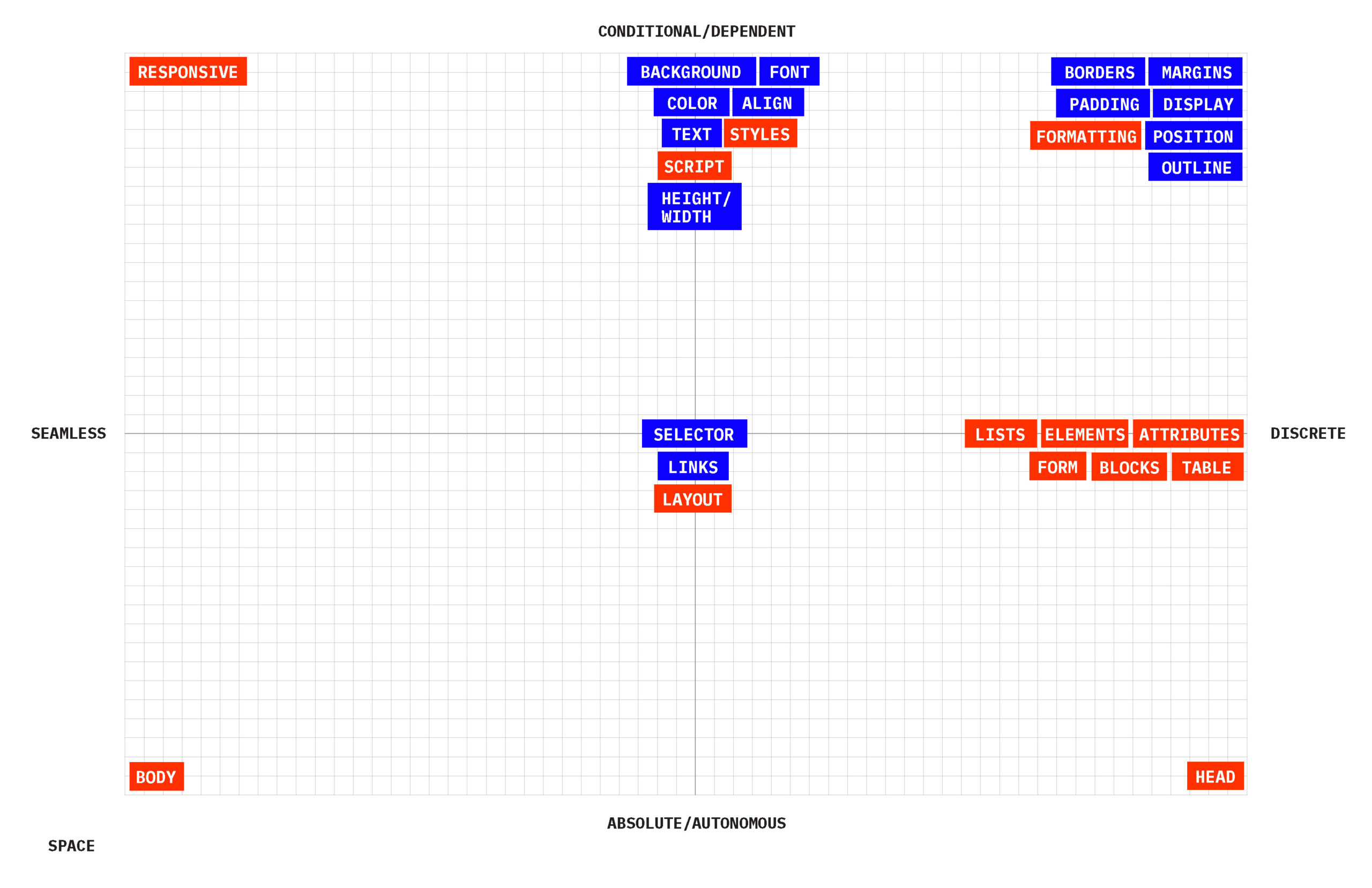

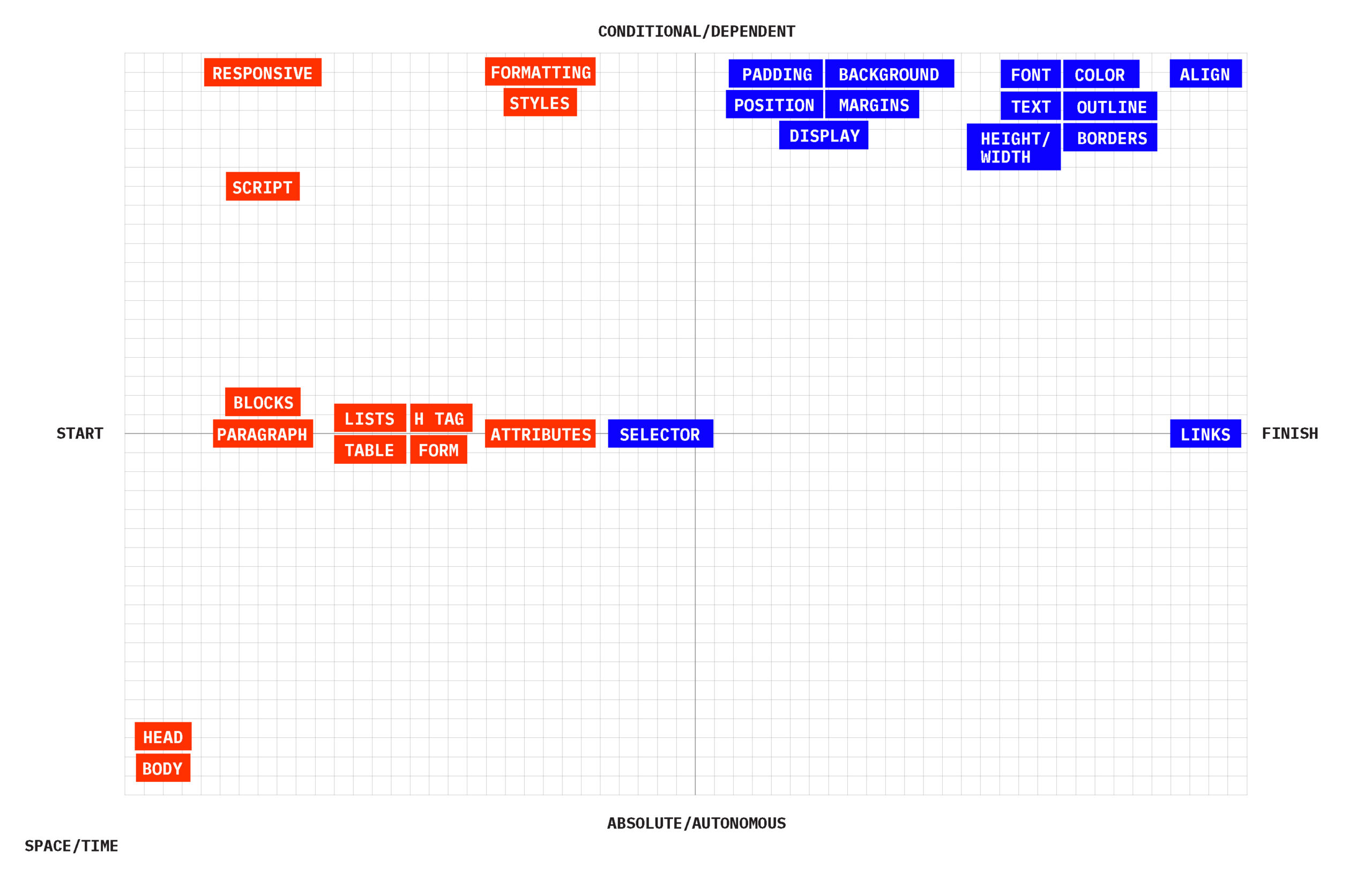

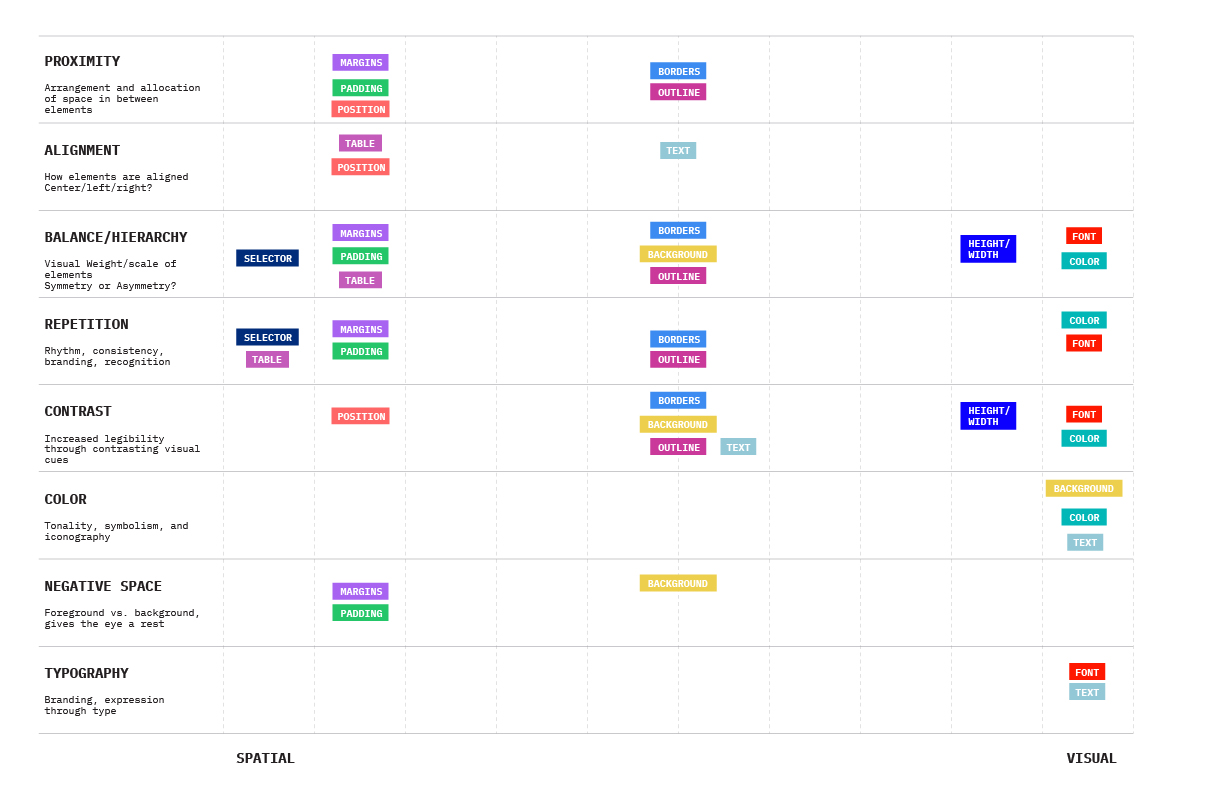

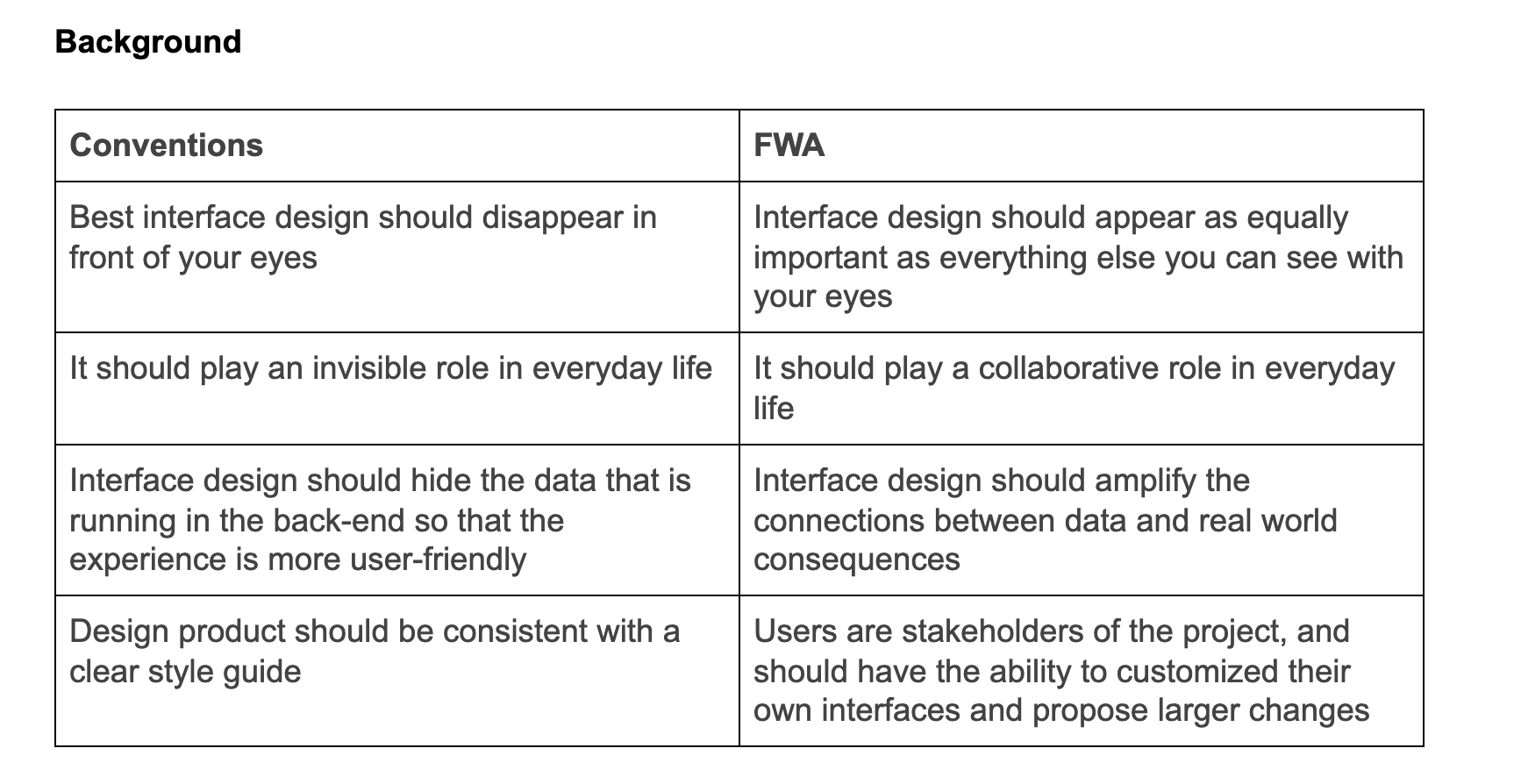

See below for early prototypes which consider CSS/HTML elements and standards in spatial and temporal terms, and the guiding principles which inform this project from the start.

Our methodology began with an objective to create transparency in the web. We researched topics and prototyped ideas that relate to browser infrastructure, an exploration of the internet as a form of time-based media, non-western design philosophies and aesthetics, the meaning of consent in digital technologies, and the complexities of digital marketing schemes and adtech. We kept a Google Doc of our research notes and findings, and held bi-weekly meetings to review our progress. In one of our meetings, we decided to focus on adtech and the issue of consent because they are so opaque to the everyday user.

Here are the main issues with adhesion contracts which pervade today's digital platforms:

- There is a lack of ample notice and a clear consent to contract;

- Digital platforms enable unlimited availability of space that permits very long and complex terms

- Contracts have extreme provisions and waiver, purposely inserted with the knowledge that users will not read them

- Embedded in digital platforms, they are used in a context marked with speed and instant gratification

Here are some common elements found in contracts that are harmful to the everyday user:

- Unilateral modification clauses which permit the creator of the contract to change or add items without notice

- Jury waiver

- Venue restrictions

- Arbitration clauses

- Transfer of intellectual property rights: Eg. In the FB user agreement, users grant “a non-exclusive, transferable, sub-licensable, royalty-free, worldwide license to use any IP content that you post on or in connection with Facebook.”

From these findings, we created a series of questions to ask ourselves to inform what we are responding to and how. One of the questions we raised was, “how much is our data worth?” As we confronted this seemingly impossible question, we also found it to be easier to estimate than we initially expected. We encountered hundreds of resources online that allows businesses to estimate the CPC of virtually any keyword imaginable. Jon Packles’ Search Record, a poetic interpretation of user data on Google Takeout, provided the technical means to finally reach our goal of estimating just how much our data is worth.

This project currently analyzes a limited number of keywords, and isn’t calculating every single keyword you have typed into Google search. On our list, the most expensive keyword is “insurance” ($54.91 USD per click) and the least expensive keyword is “pandemic” ($0.10 USD per click). You can find our expanding list of keywords here.

Resource:

Cheryl B.Preston and Eli McCann, “llewellyn Slept Here: A Short History of Sticky Contracts and Feudalism,” Oregon Law Review Vol. 91, No. 1 (2012).

See below for early prototypes which consider CSS/HTML elements and standards in spatial and temporal terms, and the guiding principles which inform this project from the start.

Our methodology began with an objective to create transparency in the web. We researched topics and prototyped ideas that relate to browser infrastructure, an exploration of the internet as a form of time-based media, non-western design philosophies and aesthetics, the meaning of consent in digital technologies, and the complexities of digital marketing schemes and adtech. We kept a Google Doc of our research notes and findings, and held bi-weekly meetings to review our progress. In one of our meetings, we decided to focus on adtech and the issue of consent because they are so opaque to the everyday user.

Here are the main issues with adhesion contracts which pervade today's digital platforms:

There is a lack of ample notice and a clear consent to contract;

Digital platforms enable unlimited availability of space that permits very long and complex terms

Contracts have extreme provisions and waiver, purposely inserted with the knowledge that users will not read them

Embedded in digital platforms, they are used in a context marked with speed and instant gratification

Here are some common elements found in contracts that are harmful to the everyday user:

Unilateral modification clauses which permit the creator of the contract to change or add items without notice

Jury waiver

Venue restrictions

Arbitration clauses

Transfer of intellectual property rights: Eg. In the FB user agreement, users grant “a non-exclusive, transferable, sub-licensable, royalty-free, worldwide license to use any IP content that you post on or in connection with Facebook.”

From these findings, we created a series of questions to ask ourselves to inform what we are responding to and how. One of the questions we raised was, “how much is our data worth?” As we confronted this seemingly impossible question, we also found it to be easier to estimate than we initially expected. We encountered hundreds of resources online that allows businesses to estimate the CPC of virtually any keyword imaginable. Jon Packles’ Search Record, a poetic interpretation of user data on Google Takeout, provided the technical means to finally reach our goal of estimating just how much our data is worth.

This project currently analyzes a limited number of keywords, and isn’t calculating every single keyword you have typed into Google search. On our list, the most expensive keyword is “insurance” ($54.91 USD per click) and the least expensive keyword is “pandemic” ($0.10 USD per click). You can find our expanding list of keywords here.

Resource:

Cheryl B.Preston and Eli McCann, “llewellyn Slept Here: A Short History of Sticky Contracts and Feudalism,” Oregon Law Review Vol. 91, No. 1 (2012).

See below for early prototypes which consider CSS/HTML elements and standards in spatial and temporal terms, and the guiding principles which inform this project from the start.

Our methodology began with an objective to create transparency in the web. We researched topics and prototyped ideas that relate to browser infrastructure, an exploration of the internet as a form of time-based media, non-western design philosophies and aesthetics, the meaning of consent in digital technologies, and the complexities of digital marketing schemes and adtech. We kept a Google Doc of our research notes and findings, and held bi-weekly meetings to review our progress. In one of our meetings, we decided to focus on adtech and the issue of consent because they are so opaque to the everyday user.

Here are the main issues with adhesion contracts which pervade today's digital platforms:

There is a lack of ample notice and a clear consent to contract;

Digital platforms enable unlimited availability of space that permits very long and complex terms

Contracts have extreme provisions and waiver, purposely inserted with the knowledge that users will not read them

Embedded in digital platforms, they are used in a context marked with speed and instant gratification

Here are some common elements found in contracts that are harmful to the everyday user:

Unilateral modification clauses which permit the creator of the contract to change or add items without notice

Jury waiver

Venue restrictions

Arbitration clauses

Transfer of intellectual property rights: Eg. In the FB user agreement, users grant “a non-exclusive, transferable, sub-licensable, royalty-free, worldwide license to use any IP content that you post on or in connection with Facebook.”

From these findings, we created a series of questions to ask ourselves to inform what we are responding to and how. One of the questions we raised was, “how much is our data worth?” As we confronted this seemingly impossible question, we also found it to be easier to estimate than we initially expected. We encountered hundreds of resources online that allows businesses to estimate the CPC of virtually any keyword imaginable. Jon Packles’ Search Record, a poetic interpretation of user data on Google Takeout, provided the technical means to finally reach our goal of estimating just how much our data is worth.

This project currently analyzes a limited number of keywords, and isn’t calculating every single keyword you have typed into Google search. On our list, the most expensive keyword is “insurance” ($54.91 USD per click) and the least expensive keyword is “pandemic” ($0.10 USD per click). You can find our expanding list of keywords here.

Resource:

Cheryl B.Preston and Eli McCann, “llewellyn Slept Here: A Short History of Sticky Contracts and Feudalism,” Oregon Law Review Vol. 91, No. 1 (2012).

See below for early prototypes which consider CSS/HTML elements and standards in spatial and temporal terms, and the guiding principles which inform this project from the start.

Our methodology began with an objective to create transparency in the web. We researched topics and prototyped ideas that relate to browser infrastructure, an exploration of the internet as a form of time-based media, non-western design philosophies and aesthetics, the meaning of consent in digital technologies, and the complexities of digital marketing schemes and adtech. We kept a Google Doc of our research notes and findings, and held bi-weekly meetings to review our progress. In one of our meetings, we decided to focus on adtech and the issue of consent because they are so opaque to the everyday user.

Here are the main issues with adhesion contracts which pervade today's digital platforms:

There is a lack of ample notice and a clear consent to contract;

Digital platforms enable unlimited availability of space that permits very long and complex terms

Contracts have extreme provisions and waiver, purposely inserted with the knowledge that users will not read them

Embedded in digital platforms, they are used in a context marked with speed and instant gratification

Here are some common elements found in contracts that are harmful to the everyday user:

Unilateral modification clauses which permit the creator of the contract to change or add items without notice

Jury waiver

Venue restrictions

Arbitration clauses

Transfer of intellectual property rights: Eg. In the FB user agreement, users grant “a non-exclusive, transferable, sub-licensable, royalty-free, worldwide license to use any IP content that you post on or in connection with Facebook.”

From these findings, we created a series of questions to ask ourselves to inform what we are responding to and how. One of the questions we raised was, “how much is our data worth?” As we confronted this seemingly impossible question, we also found it to be easier to estimate than we initially expected. We encountered hundreds of resources online that allows businesses to estimate the CPC of virtually any keyword imaginable. Jon Packles’ Search Record, a poetic interpretation of user data on Google Takeout, provided the technical means to finally reach our goal of estimating just how much our data is worth.

This project currently analyzes a limited number of keywords, and isn’t calculating every single keyword you have typed into Google search. On our list, the most expensive keyword is “insurance” ($54.91 USD per click) and the least expensive keyword is “pandemic” ($0.10 USD per click). You can find our expanding list of keywords here.

Resource:

Cheryl B.Preston and Eli McCann, “llewellyn Slept Here: A Short History of Sticky Contracts and Feudalism,” Oregon Law Review Vol. 91, No. 1 (2012).

See below for early prototypes which consider CSS/HTML elements and standards in spatial and temporal terms, and the guiding principles which inform this project from the start.