The Unspoken Monument

The Unspoken Monument

The Unspoken Monument

The Unspoken Monument

The Unspoken Monument

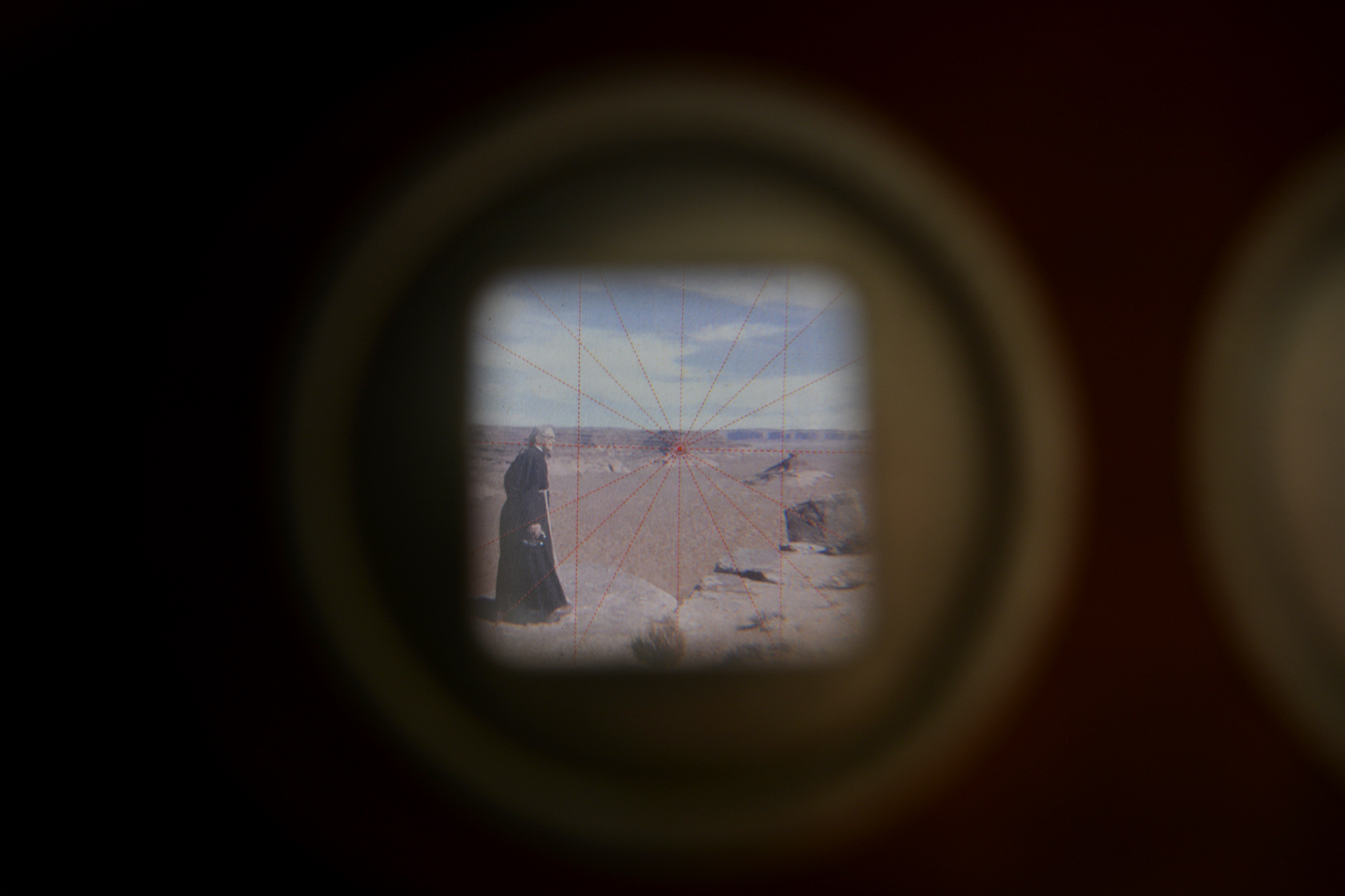

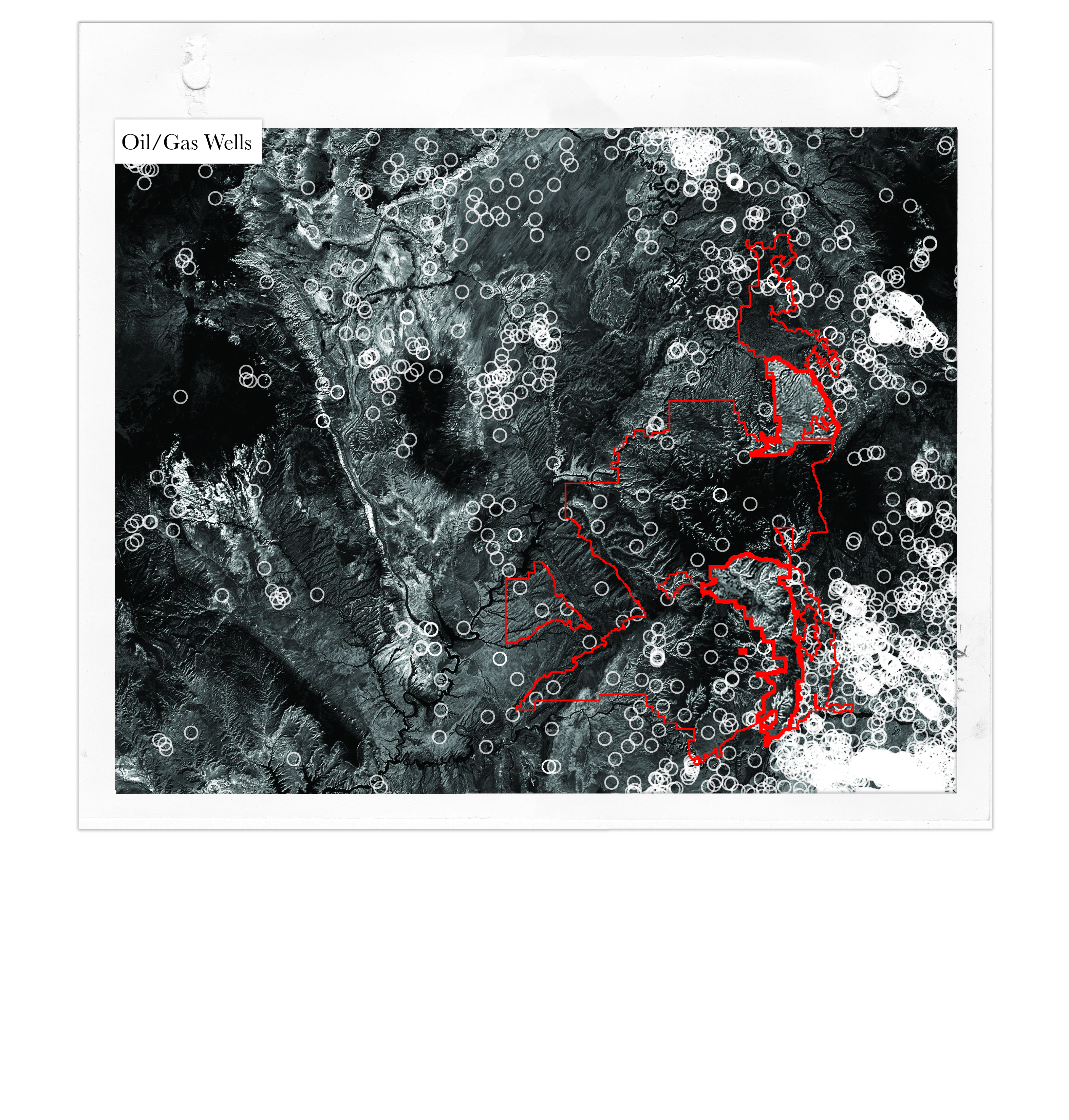

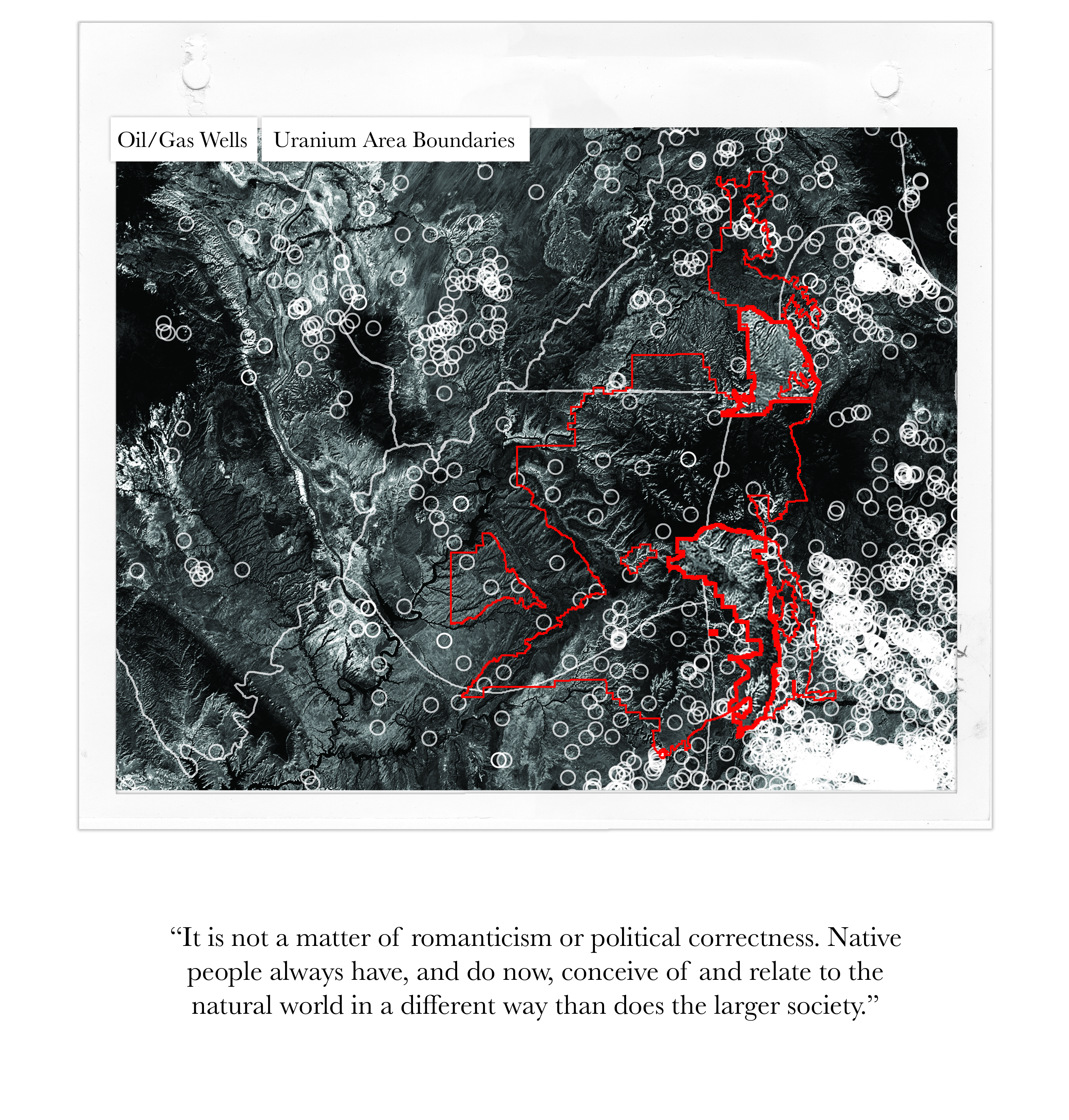

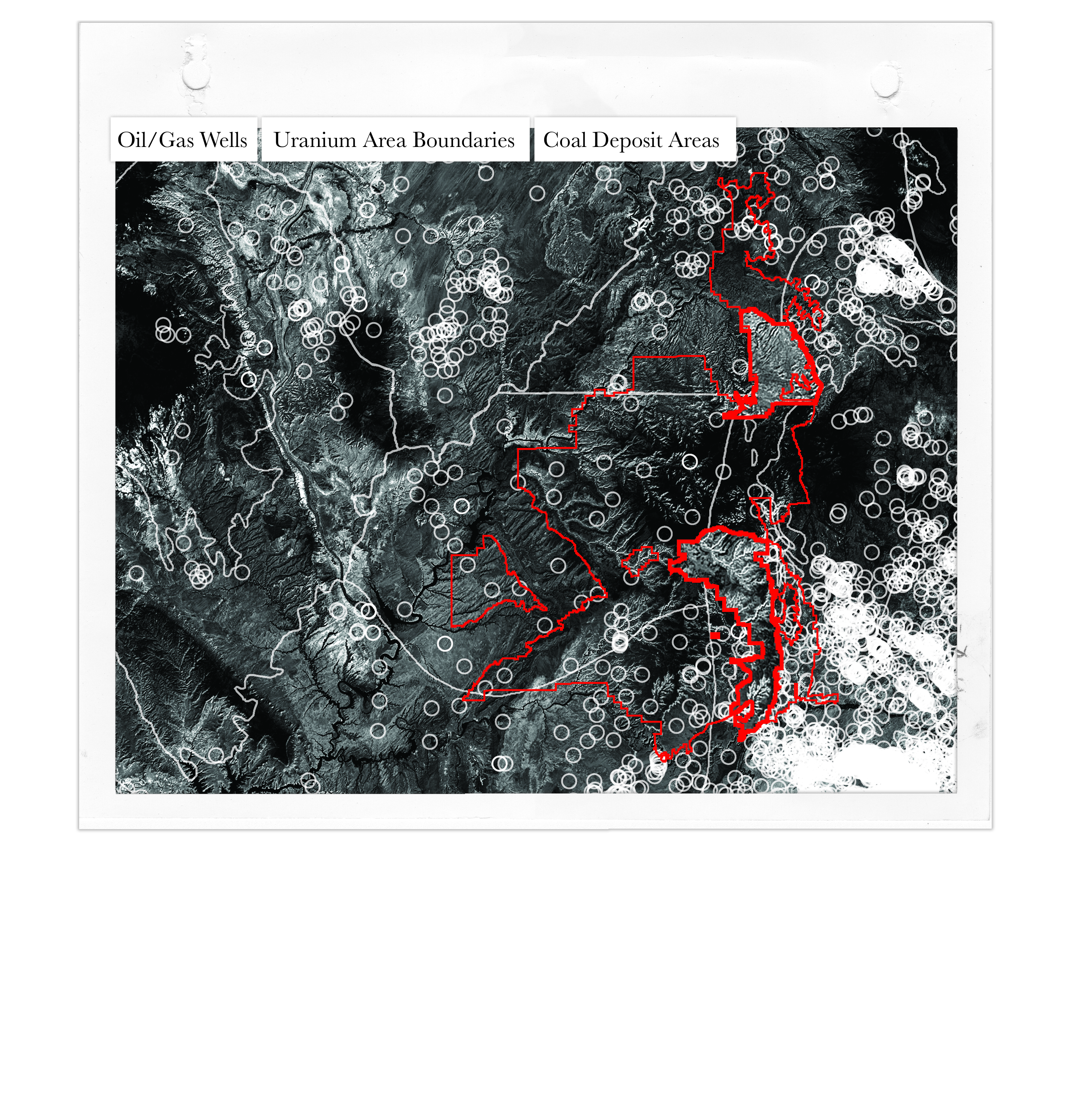

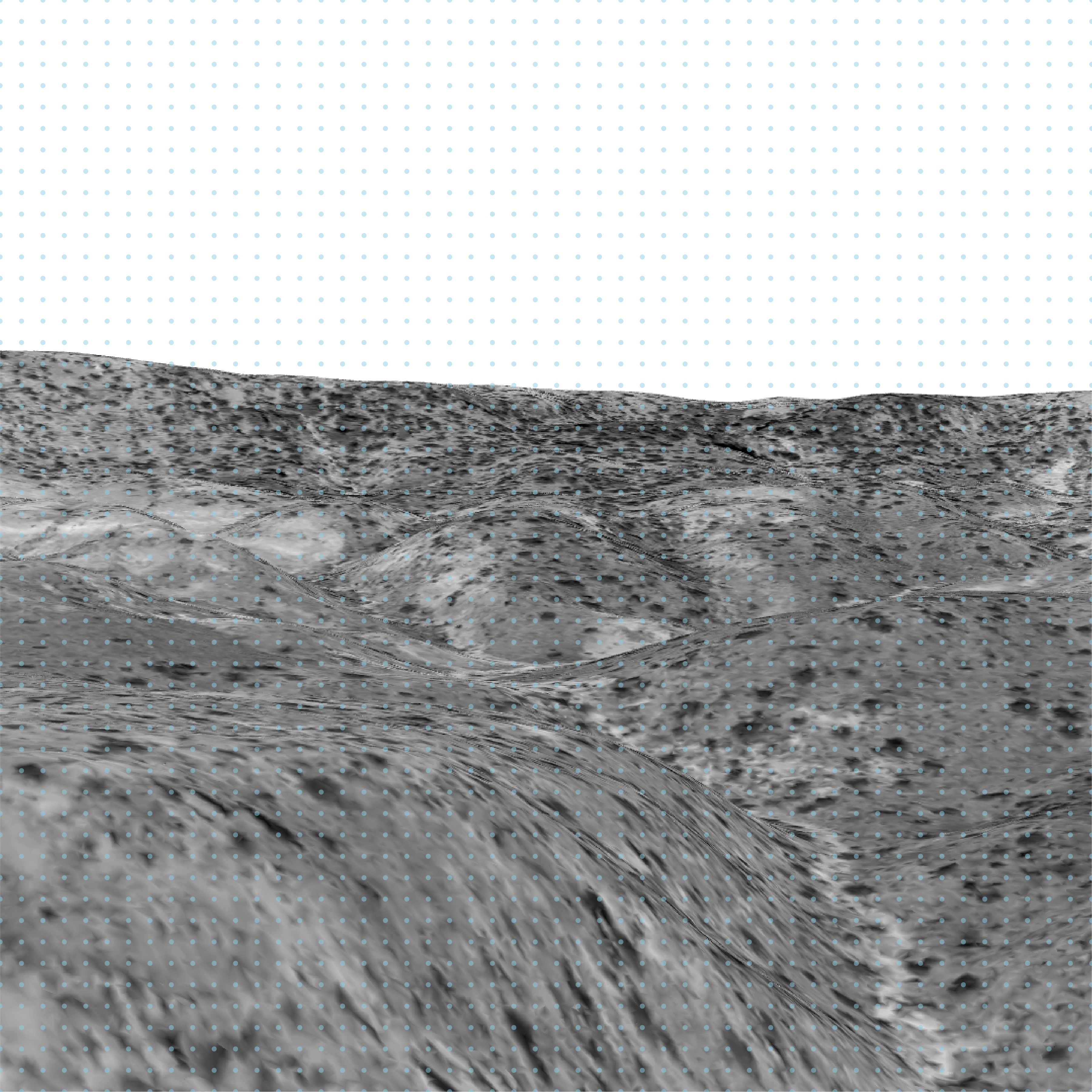

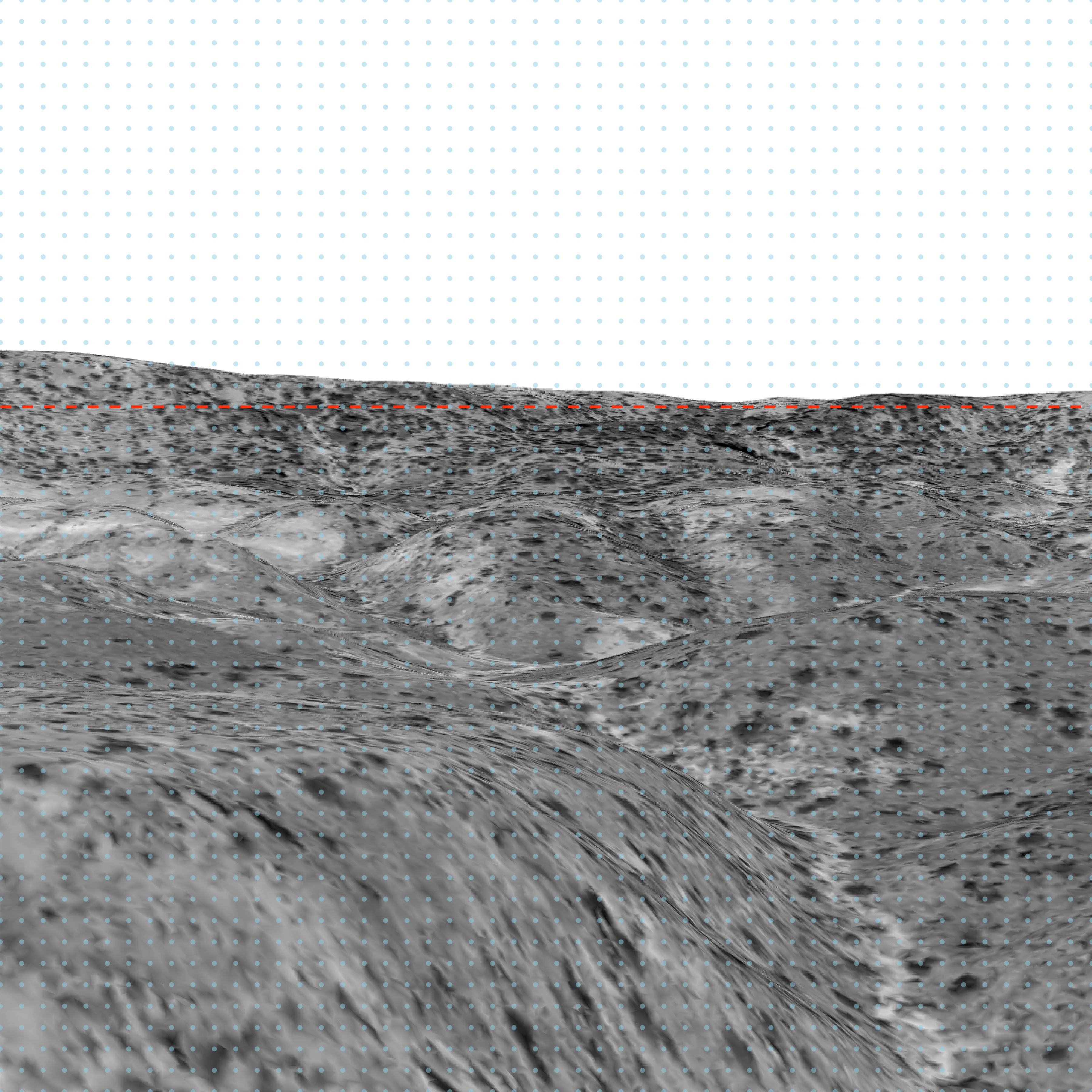

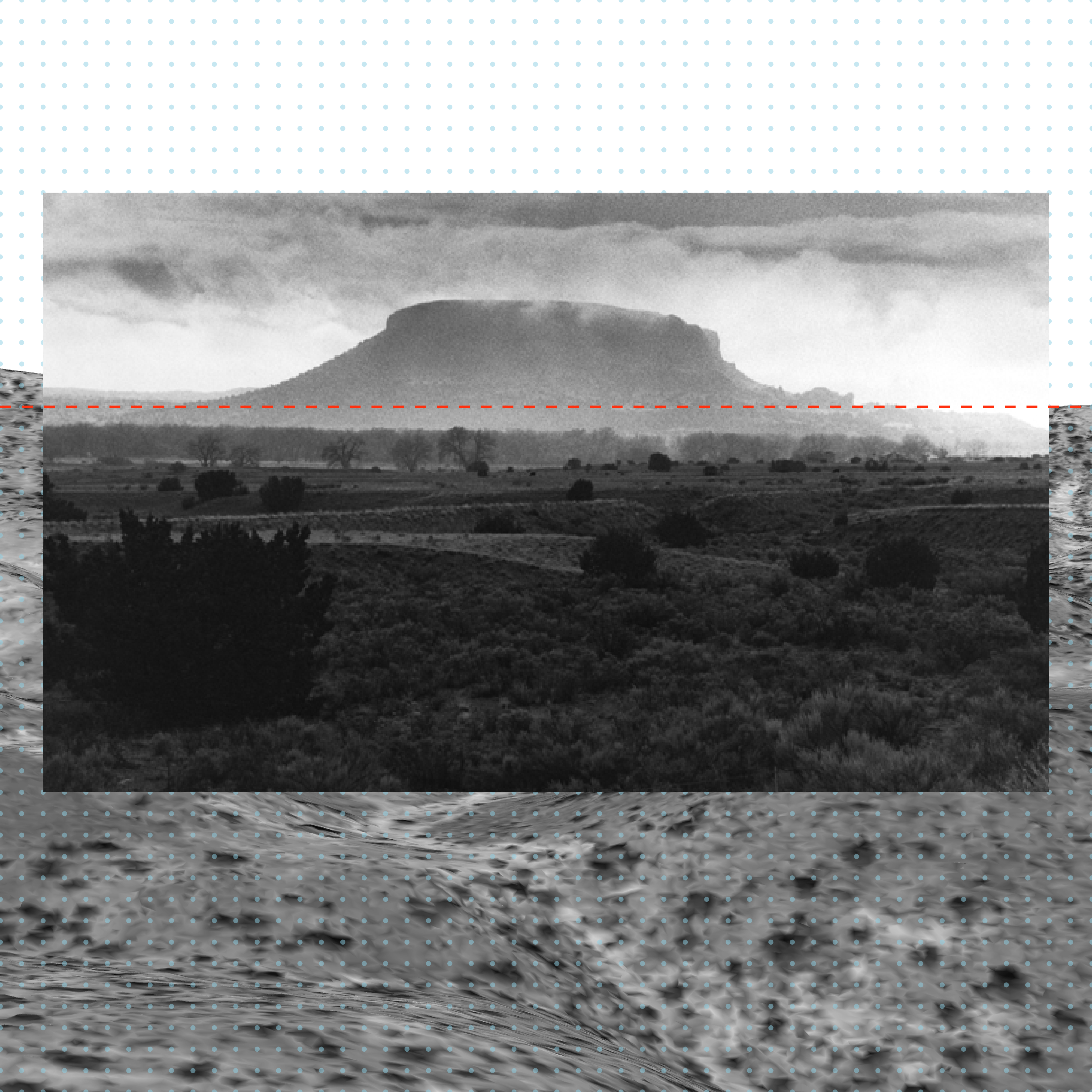

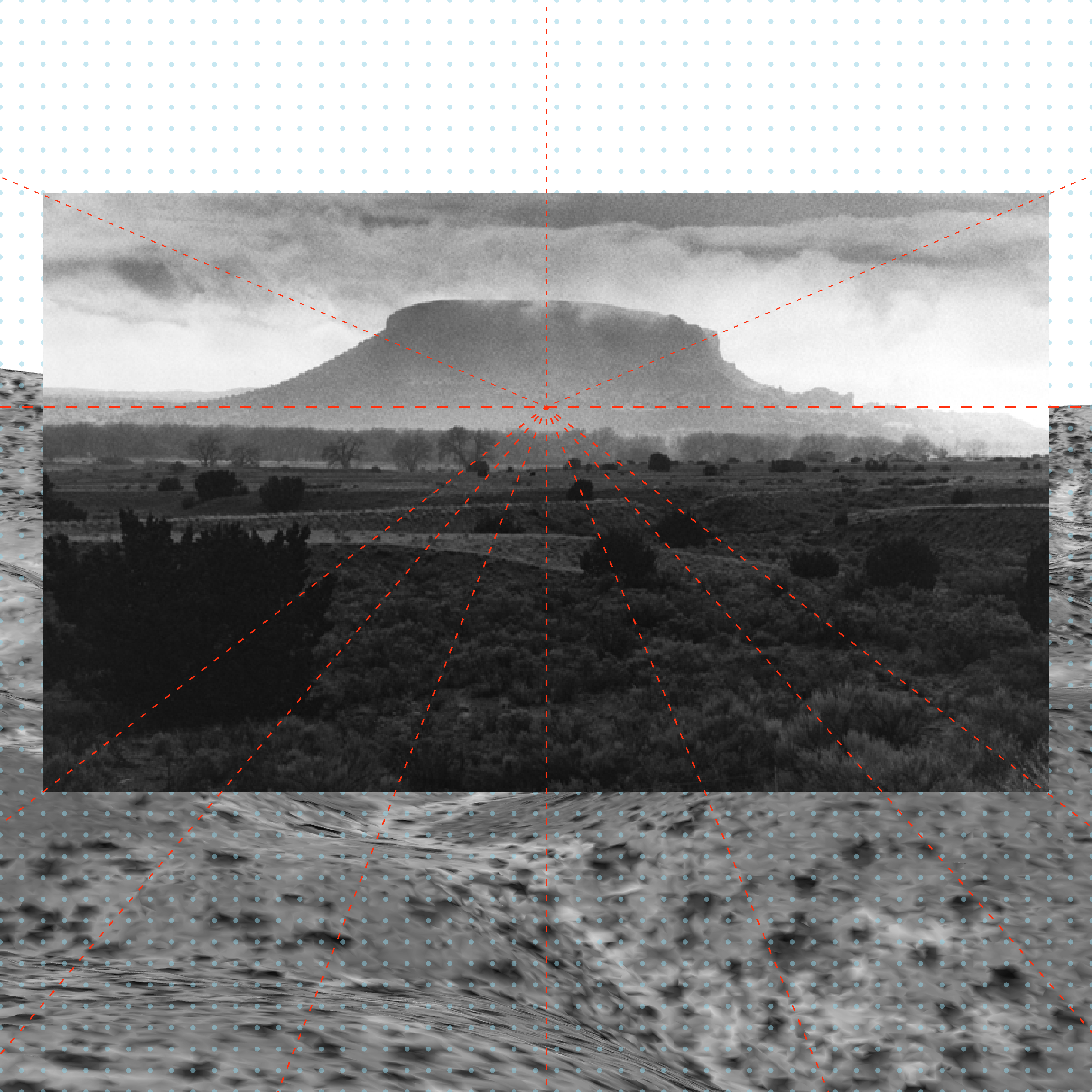

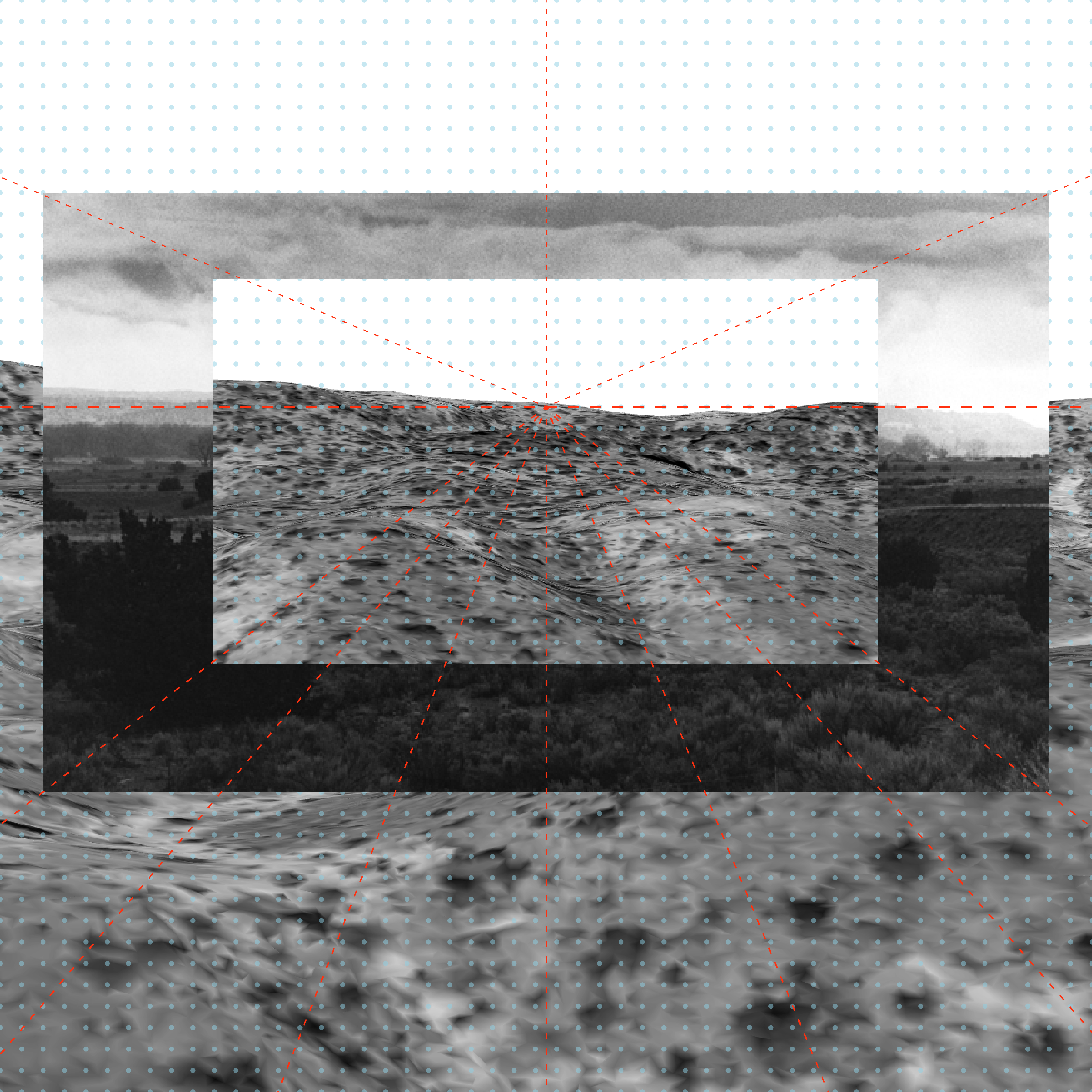

The Unspoken Monument is both a monument to the unmarked intersections between histories that make up Bears Ears National Monument, and a viewing device with which one can experience, and examine the landscape. The use of archival documents of opposing perspectives act as evidence to prove how subtraction and extraction fit into the formation of the monument, and how its Native population has been contained and controlled by a white ruling class. Linear and aerial perspectives are employed as visual techniques to suggest that nature has been made a calculable, predictable, and therefore manageable idea, and how this informed the formation of landscape as an idea. Through the abstraction of reality on one hand, and the privilege of an omnipresent God’s eye view on the other, linear and aerial perspectives have shaped, and continue to shape the representation and understanding of landscape.

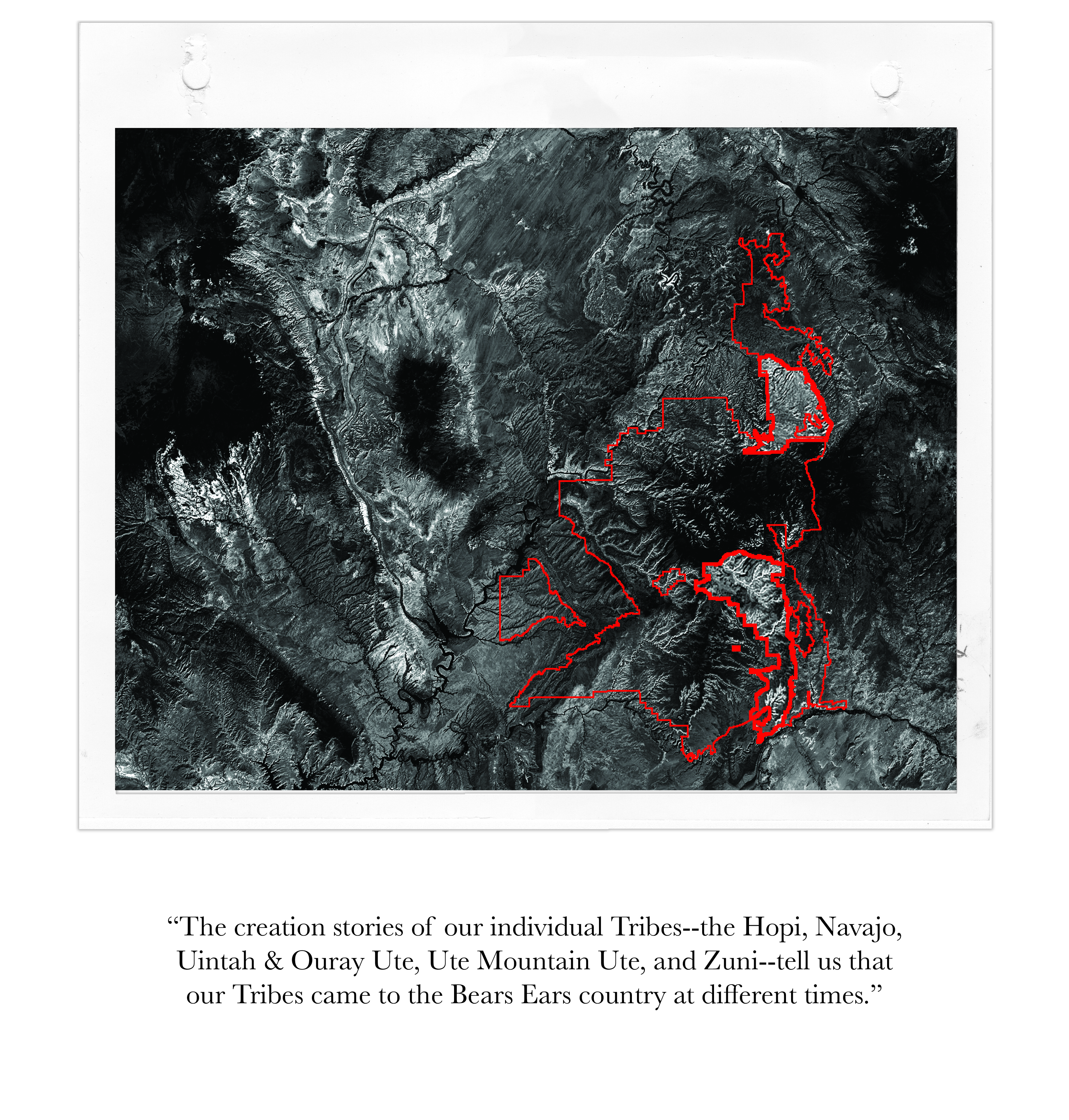

Bears Ears National Monument was established on December 28, 2016 by President Obama. The proposal was led by coalition of five tribes who have ancestral ties to the land: the Navajo, Hopi, Zuni, Ute Mountain Ute Tribe and Ute Indian Tribe. The established boundary encompassing 1.35 million acres was a compromise to the 1.9 million acre proposed by the tribes. Short of a year later, and without the collaboration of tribal leadership, Trump reduced the monument by 85%, and established two non-contiguous monuments covering a mere 201,876 acres: Indian Creek and Shash Jáa.

The Unspoken Monument is both a monument to the unmarked intersections between histories that make up Bears Ears National Monument, and a viewing device with which one can experience, and examine the landscape. The use of archival documents of opposing perspectives act as evidence to prove how subtraction and extraction fit into the formation of the monument, and how its Native population has been contained and controlled by a white ruling class. Linear and aerial perspectives are employed as visual techniques to suggest that nature has been made a calculable, predictable, and therefore manageable idea, and how this informed the formation of landscape as an idea. Through the abstraction of reality on one hand, and the privilege of an omnipresent God’s eye view on the other, linear and aerial perspectives have shaped, and continue to shape the representation and understanding of landscape.

Bears Ears National Monument was established on December 28, 2016 by President Obama. The proposal was led by coalition of five tribes who have ancestral ties to the land: the Navajo, Hopi, Zuni, Ute Mountain Ute Tribe and Ute Indian Tribe. The established boundary encompassing 1.35 million acres was a compromise to the 1.9 million acre proposed by the tribes. Short of a year later, and without the collaboration of tribal leadership, Trump reduced the monument by 85%, and established two non-contiguous monuments covering a mere 201,876 acres: Indian Creek and Shash Jáa.

The Unspoken Monument is both a monument to the unmarked intersections between histories that make up Bears Ears National Monument, and a viewing device with which one can experience, and examine the landscape. The use of archival documents of opposing perspectives act as evidence to prove how subtraction and extraction fit into the formation of the monument, and how its Native population has been contained and controlled by a white ruling class. Linear and aerial perspectives are employed as visual techniques to suggest that nature has been made a calculable, predictable, and therefore manageable idea, and how this informed the formation of landscape as an idea. Through the abstraction of reality on one hand, and the privilege of an omnipresent God’s eye view on the other, linear and aerial perspectives have shaped, and continue to shape the representation and understanding of landscape.

Bears Ears National Monument was established on December 28, 2016 by President Obama. The proposal was led by coalition of five tribes who have ancestral ties to the land: the Navajo, Hopi, Zuni, Ute Mountain Ute Tribe and Ute Indian Tribe. The established boundary encompassing 1.35 million acres was a compromise to the 1.9 million acre proposed by the tribes. Short of a year later, and without the collaboration of tribal leadership, Trump reduced the monument by 85%, and established two non-contiguous monuments covering a mere 201,876 acres: Indian Creek and Shash Jáa.

The Unspoken Monument is both a monument to the unmarked intersections between histories that make up Bears Ears National Monument, and a viewing device with which one can experience, and examine the landscape. The use of archival documents of opposing perspectives act as evidence to prove how subtraction and extraction fit into the formation of the monument, and how its Native population has been contained and controlled by a white ruling class. Linear and aerial perspectives are employed as visual techniques to suggest that nature has been made a calculable, predictable, and therefore manageable idea, and how this informed the formation of landscape as an idea. Through the abstraction of reality on one hand, and the privilege of an omnipresent God’s eye view on the other, linear and aerial perspectives have shaped, and continue to shape the representation and understanding of landscape.

Bears Ears National Monument was established on December 28, 2016 by President Obama. The proposal was led by coalition of five tribes who have ancestral ties to the land: the Navajo, Hopi, Zuni, Ute Mountain Ute Tribe and Ute Indian Tribe. The established boundary encompassing 1.35 million acres was a compromise to the 1.9 million acre proposed by the tribes. Short of a year later, and without the collaboration of tribal leadership, Trump reduced the monument by 85%, and established two non-contiguous monuments covering a mere 201,876 acres: Indian Creek and Shash Jáa.

The Unspoken Monument is both a monument to the unmarked intersections between histories that make up Bears Ears National Monument, and a viewing device with which one can experience, and examine the landscape. The use of archival documents of opposing perspectives act as evidence to prove how subtraction and extraction fit into the formation of the monument, and how its Native population has been contained and controlled by a white ruling class. Linear and aerial perspectives are employed as visual techniques to suggest that nature has been made a calculable, predictable, and therefore manageable idea, and how this informed the formation of landscape as an idea. Through the abstraction of reality on one hand, and the privilege of an omnipresent God’s eye view on the other, linear and aerial perspectives have shaped, and continue to shape the representation and understanding of landscape.

Bears Ears National Monument was established on December 28, 2016 by President Obama. The proposal was led by coalition of five tribes who have ancestral ties to the land: the Navajo, Hopi, Zuni, Ute Mountain Ute Tribe and Ute Indian Tribe. The established boundary encompassing 1.35 million acres was a compromise to the 1.9 million acre proposed by the tribes. Short of a year later, and without the collaboration of tribal leadership, Trump reduced the monument by 85%, and established two non-contiguous monuments covering a mere 201,876 acres: Indian Creek and Shash Jáa.

According to Sarah Lewis in The Future Perfect: Race and Monuments in the United States, monuments have the potential to shift us to a conditional tense: the future real conditional, or “what must have had to happen here.” This conditional tense, not only involves the consideration of history, but “living the future now, as an imperative,” and “striving for the future you want to see.” As she compares the positioning and placement of the Martin Luther King Jr. memorial, and the Jefferson memorial in Washington, DC, she argues that the juxtaposition of these statues functions as a monument, or “a performance of a future that hasn’t yet happened, but must.” This project is an attempt to show how monuments can be self-reflexive, mirroring back to us an unspoken element that is revealed by the convergence of opposing perspectives; that they can transcend us from the past to a future we want to live.

Bears Ears National Monument in southeastern Utah is a contested landscape of various historical, political and physiological extremes. It is a space which exists between the solid and void, the qualitative and quantitative, and the sacred and material. The erratic landscape corresponds with an erratic social reality as if nothing else could have happened there; so, “what must have had to happen here?” Again, the convergence of conflicting narratives within a monument mirrors the unspoken: the existence of this place coincides with the displacement of people, and the subjugation of nature. This mirrored image of the past and the present reveals the dichotomy between those occupying power and the subjects of that power; and this convergence situates us into considering, what must happen here in the future.

According to Sarah Lewis in The Future Perfect: Race and Monuments in the United States, monuments have the potential to shift us to a conditional tense: the future real conditional, or “what must have had to happen here.” This conditional tense, not only involves the consideration of history, but “living the future now, as an imperative,” and “striving for the future you want to see.” As she compares the positioning and placement of the Martin Luther King Jr. memorial, and the Jefferson memorial in Washington, DC, she argues that the juxtaposition of these statues functions as a monument, or “a performance of a future that hasn’t yet happened, but must.” This project is an attempt to show how monuments can be self-reflexive, mirroring back to us an unspoken element that is revealed by the convergence of opposing perspectives; that they can transcend us from the past to a future we want to live.

Bears Ears National Monument in southeastern Utah is a contested landscape of various historical, political and physiological extremes. It is a space which exists between the solid and void, the qualitative and quantitative, and the sacred and material. The erratic landscape corresponds with an erratic social reality as if nothing else could have happened there; so, “what must have had to happen here?” Again, the convergence of conflicting narratives within a monument mirrors the unspoken: the existence of this place coincides with the displacement of people, and the subjugation of nature. This mirrored image of the past and the present reveals the dichotomy between those occupying power and the subjects of that power; and this convergence situates us into considering, what must happen here in the future.

According to Sarah Lewis in The Future Perfect: Race and Monuments in the United States, monuments have the potential to shift us to a conditional tense: the future real conditional, or “what must have had to happen here.” This conditional tense, not only involves the consideration of history, but “living the future now, as an imperative,” and “striving for the future you want to see.” As she compares the positioning and placement of the Martin Luther King Jr. memorial, and the Jefferson memorial in Washington, DC, she argues that the juxtaposition of these statues functions as a monument, or “a performance of a future that hasn’t yet happened, but must.” This project is an attempt to show how monuments can be self-reflexive, mirroring back to us an unspoken element that is revealed by the convergence of opposing perspectives; that they can transcend us from the past to a future we want to live.

Bears Ears National Monument in southeastern Utah is a contested landscape of various historical, political and physiological extremes. It is a space which exists between the solid and void, the qualitative and quantitative, and the sacred and material. The erratic landscape corresponds with an erratic social reality as if nothing else could have happened there; so, “what must have had to happen here?” Again, the convergence of conflicting narratives within a monument mirrors the unspoken: the existence of this place coincides with the displacement of people, and the subjugation of nature. This mirrored image of the past and the present reveals the dichotomy between those occupying power and the subjects of that power; and this convergence situates us into considering, what must happen here in the future.

According to Sarah Lewis in The Future Perfect: Race and Monuments in the United States, monuments have the potential to shift us to a conditional tense: the future real conditional, or “what must have had to happen here.” This conditional tense, not only involves the consideration of history, but “living the future now, as an imperative,” and “striving for the future you want to see.” As she compares the positioning and placement of the Martin Luther King Jr. memorial, and the Jefferson memorial in Washington, DC, she argues that the juxtaposition of these statues functions as a monument, or “a performance of a future that hasn’t yet happened, but must.” This project is an attempt to show how monuments can be self-reflexive, mirroring back to us an unspoken element that is revealed by the convergence of opposing perspectives; that they can transcend us from the past to a future we want to live.

Bears Ears National Monument in southeastern Utah is a contested landscape of various historical, political and physiological extremes. It is a space which exists between the solid and void, the qualitative and quantitative, and the sacred and material. The erratic landscape corresponds with an erratic social reality as if nothing else could have happened there; so, “what must have had to happen here?” Again, the convergence of conflicting narratives within a monument mirrors the unspoken: the existence of this place coincides with the displacement of people, and the subjugation of nature. This mirrored image of the past and the present reveals the dichotomy between those occupying power and the subjects of that power; and this convergence situates us into considering, what must happen here in the future.

According to Sarah Lewis in The Future Perfect: Race and Monuments in the United States, monuments have the potential to shift us to a conditional tense: the future real conditional, or “what must have had to happen here.” This conditional tense, not only involves the consideration of history, but “living the future now, as an imperative,” and “striving for the future you want to see.” As she compares the positioning and placement of the Martin Luther King Jr. memorial, and the Jefferson memorial in Washington, DC, she argues that the juxtaposition of these statues functions as a monument, or “a performance of a future that hasn’t yet happened, but must.” Monuments can be self-reflexive, mirroring back to us an unspoken element that is revealed by the convergence of opposing perspectives; they can transcend us from the past to a future we want to live.

Bears Ears National Monument in southeastern Utah is a contested landscape of various historical, political and physiological extremes. It is a space which exists between the solid and void, the qualitative and quantitative, and the sacred and material. The erratic landscape corresponds with an erratic social reality as if nothing else could have happened there; so, “what must have had to happen here?” Again, the convergence of conflicting narratives within a monument mirrors the unspoken: the existence of this place coincides with the displacement of people, and the subjugation of nature. This mirrored image of the past and the present reveals the dichotomy between those occupying power and the subjects of that power; and this convergence situates us into considering, what must happen here in the future.

Sources:

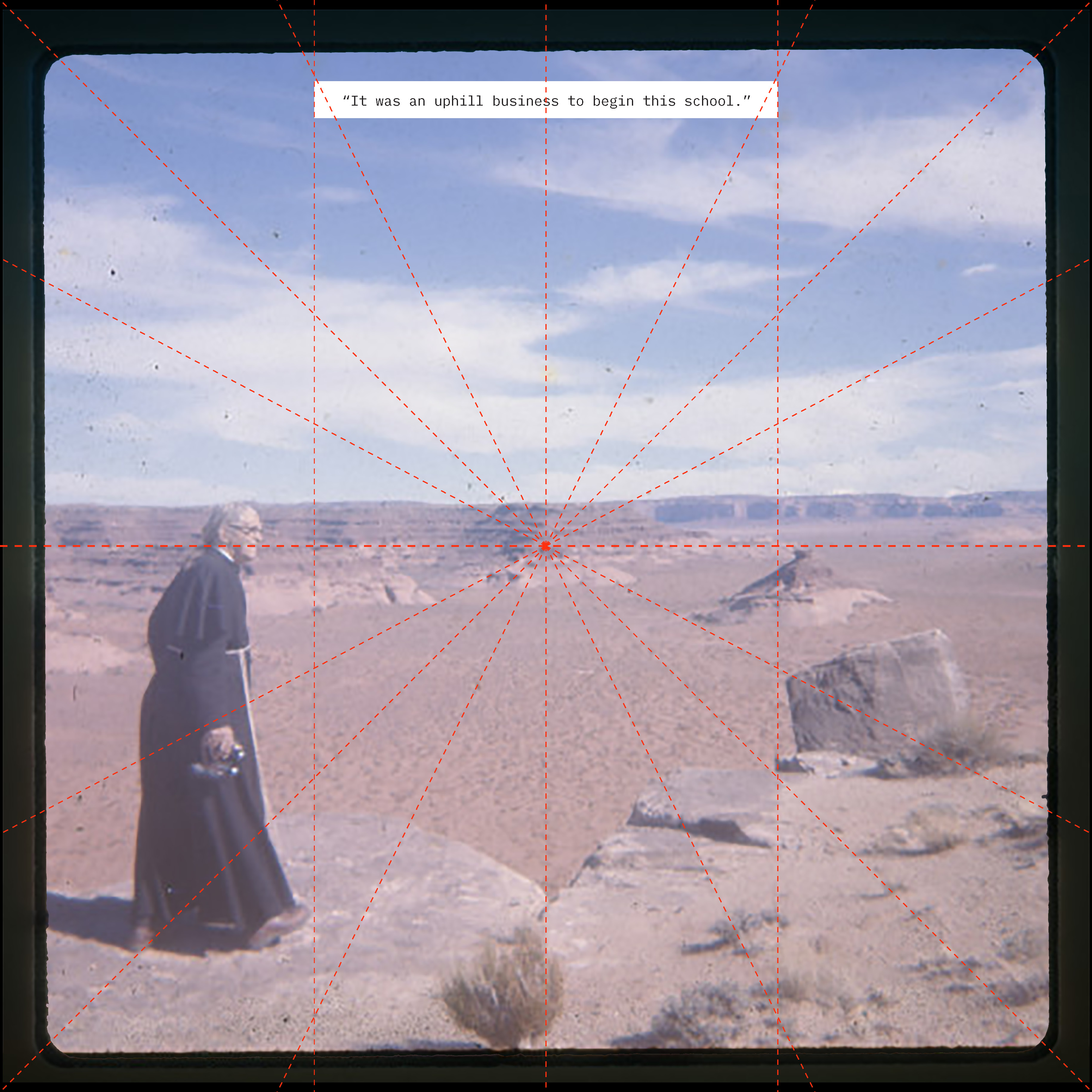

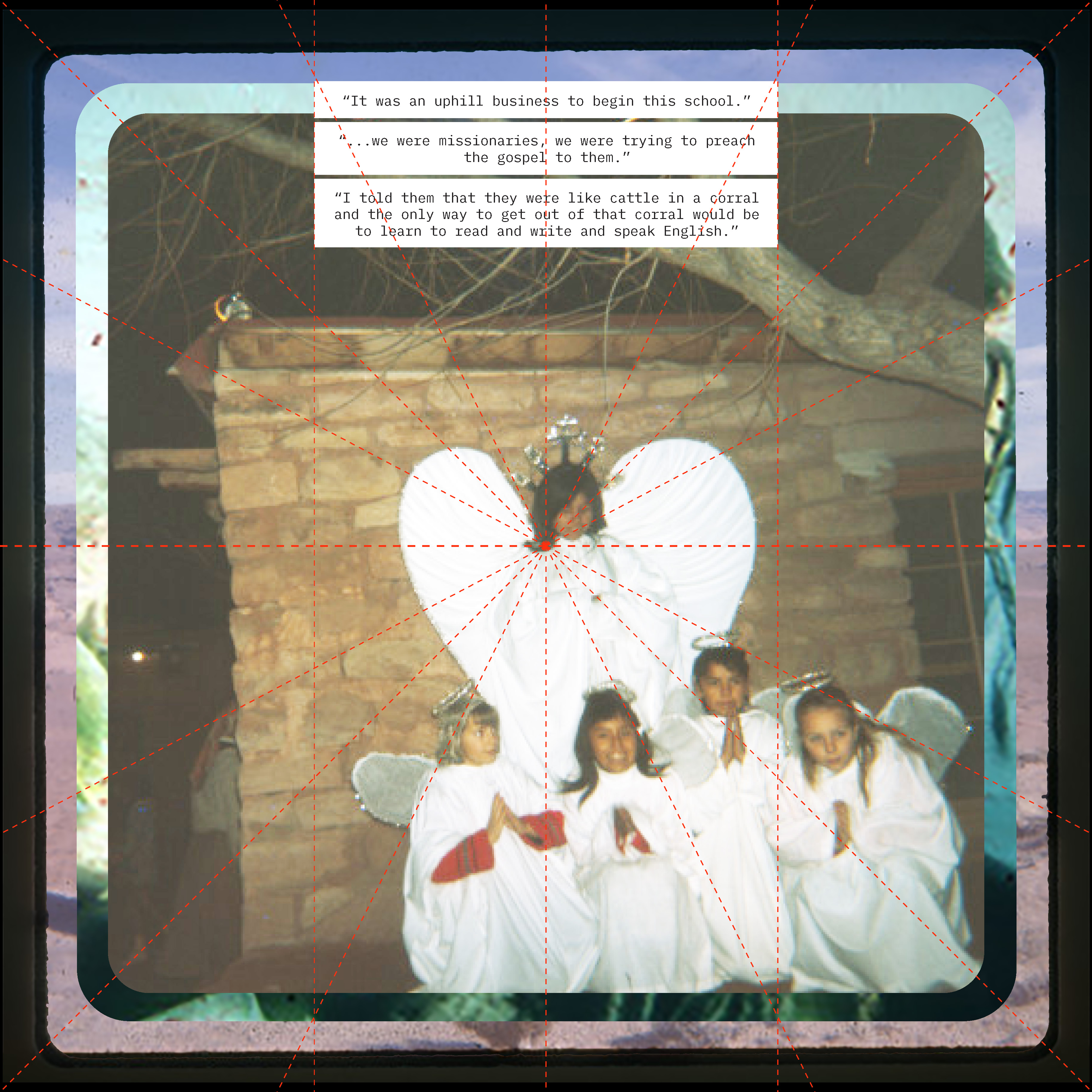

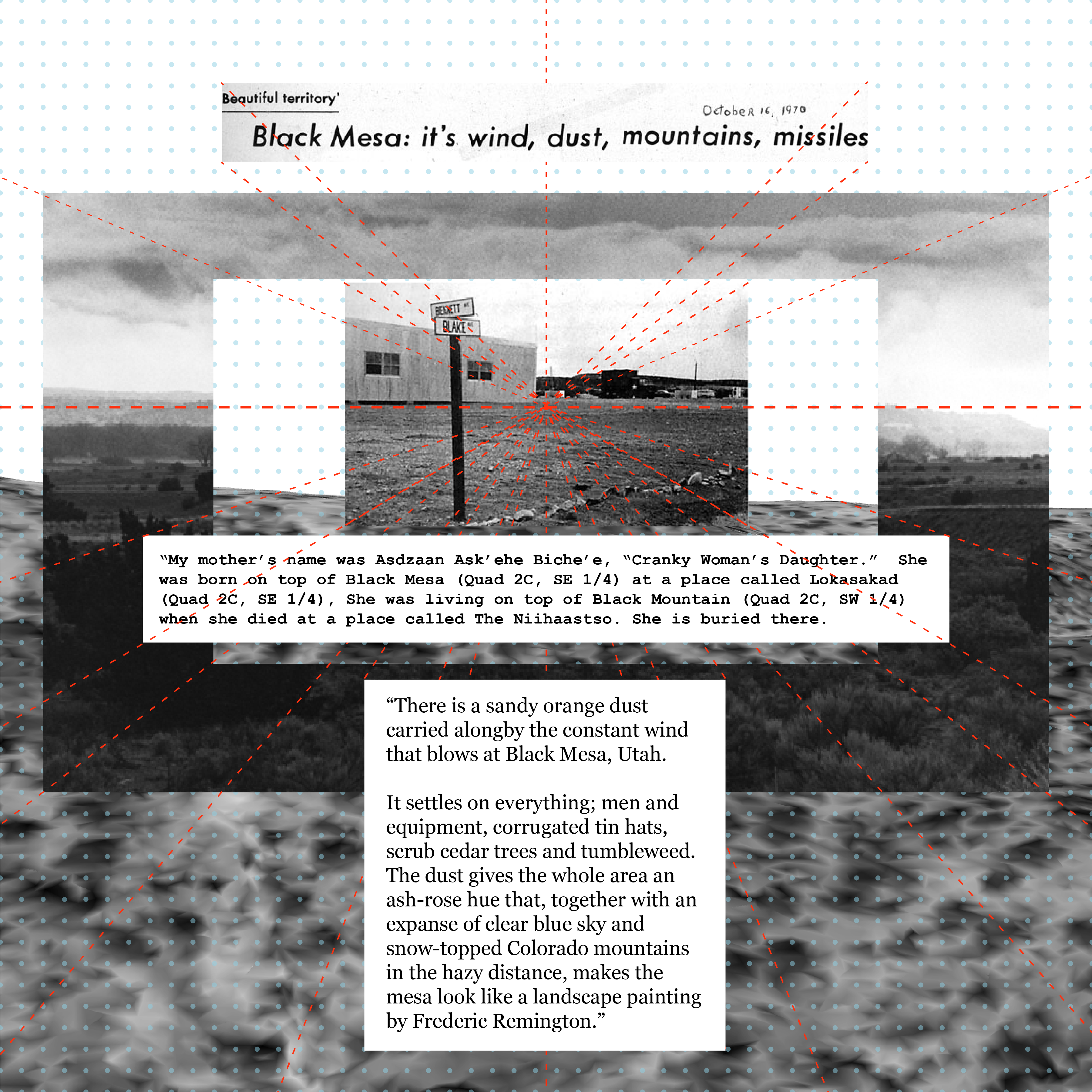

A0001 Doris Duke, 0399, Albert L. Lyman (1968), Special Collections, J.Willard Marriott Library, The University of Utah

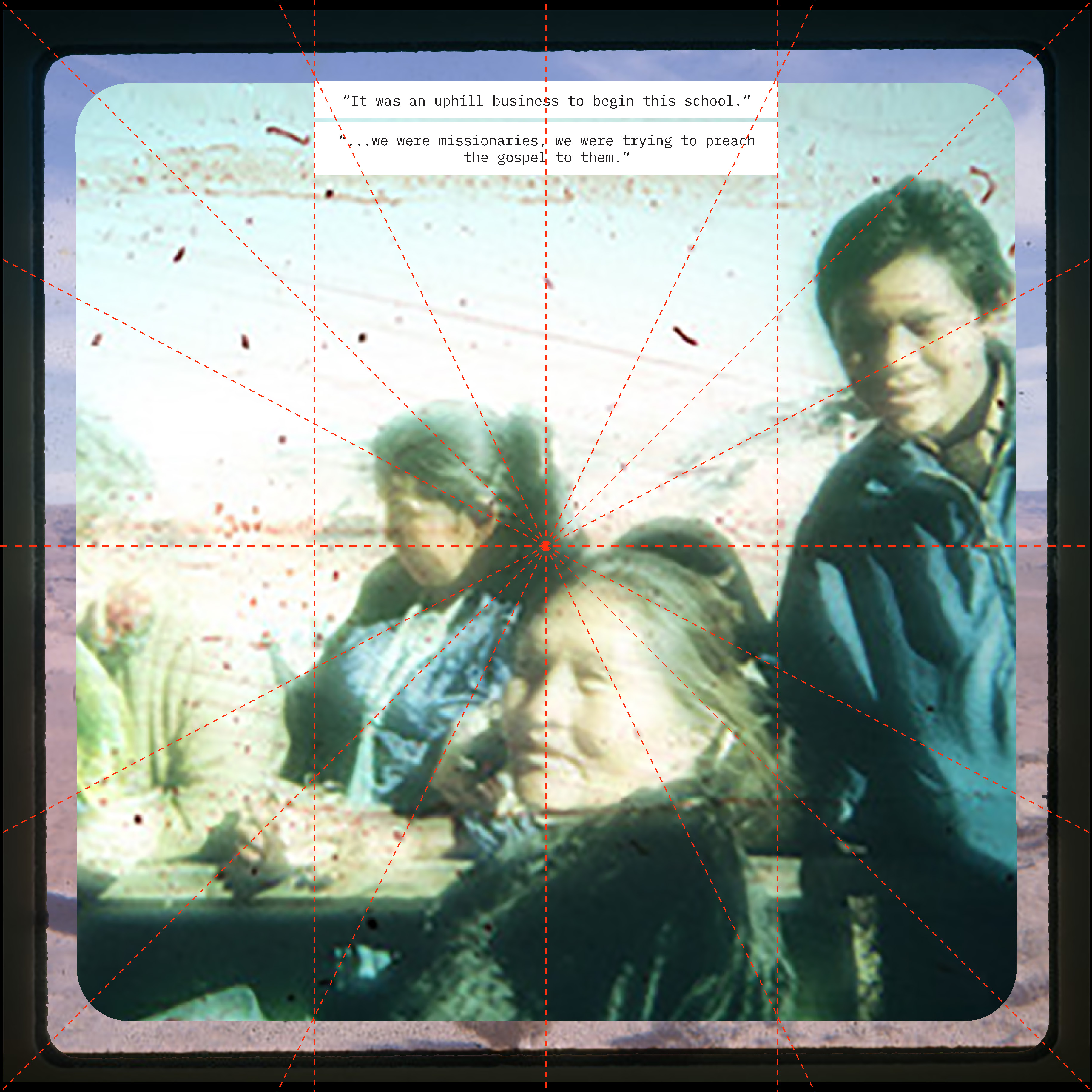

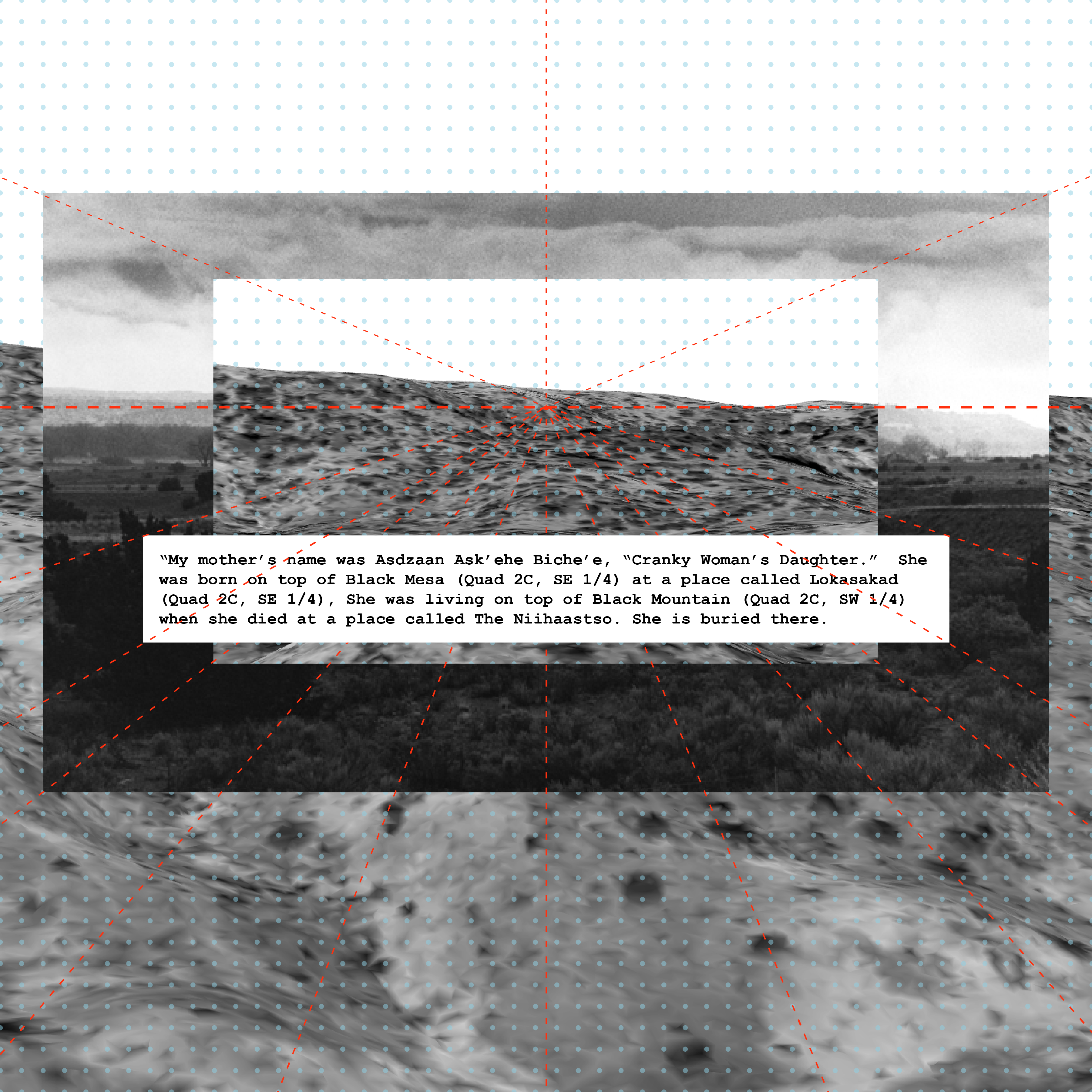

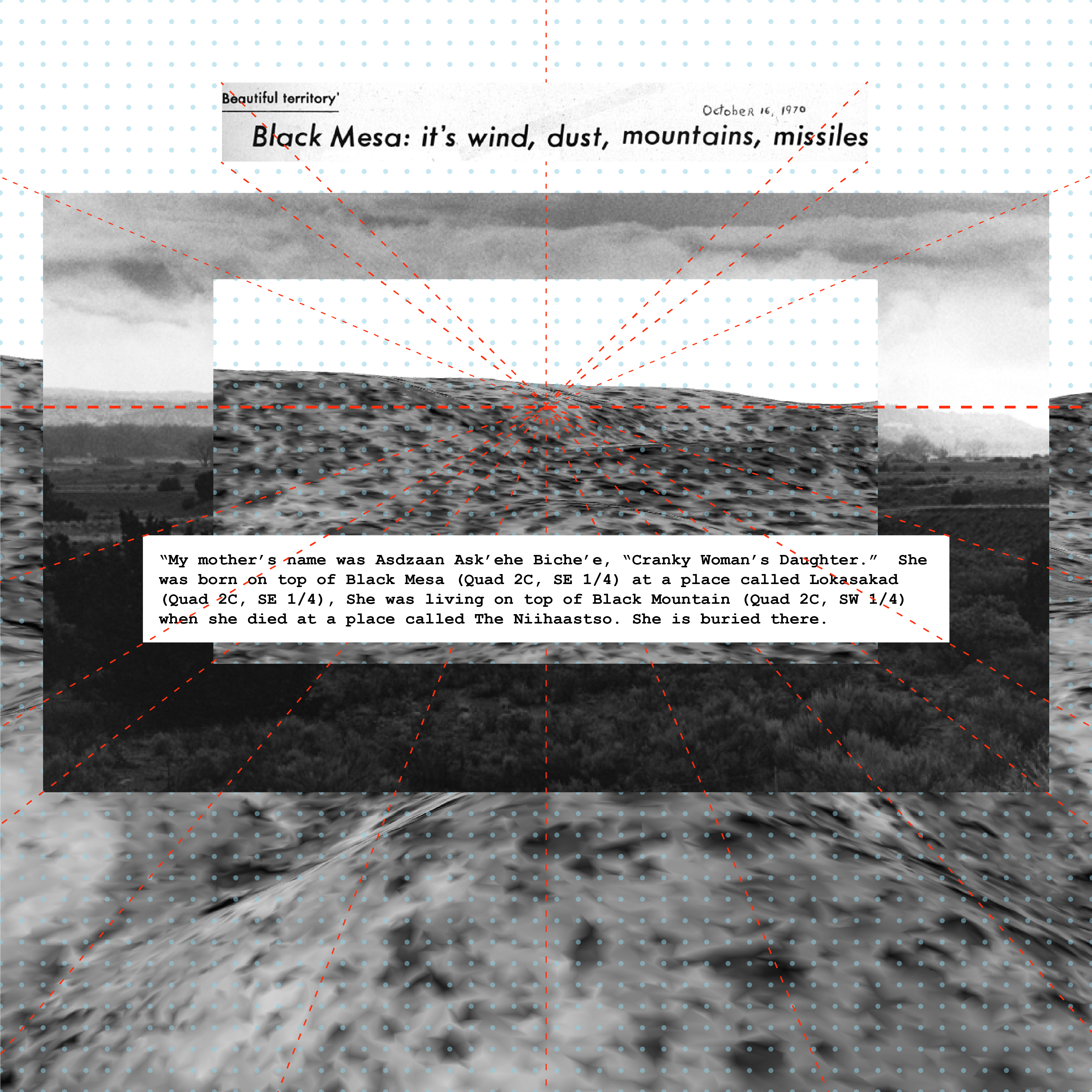

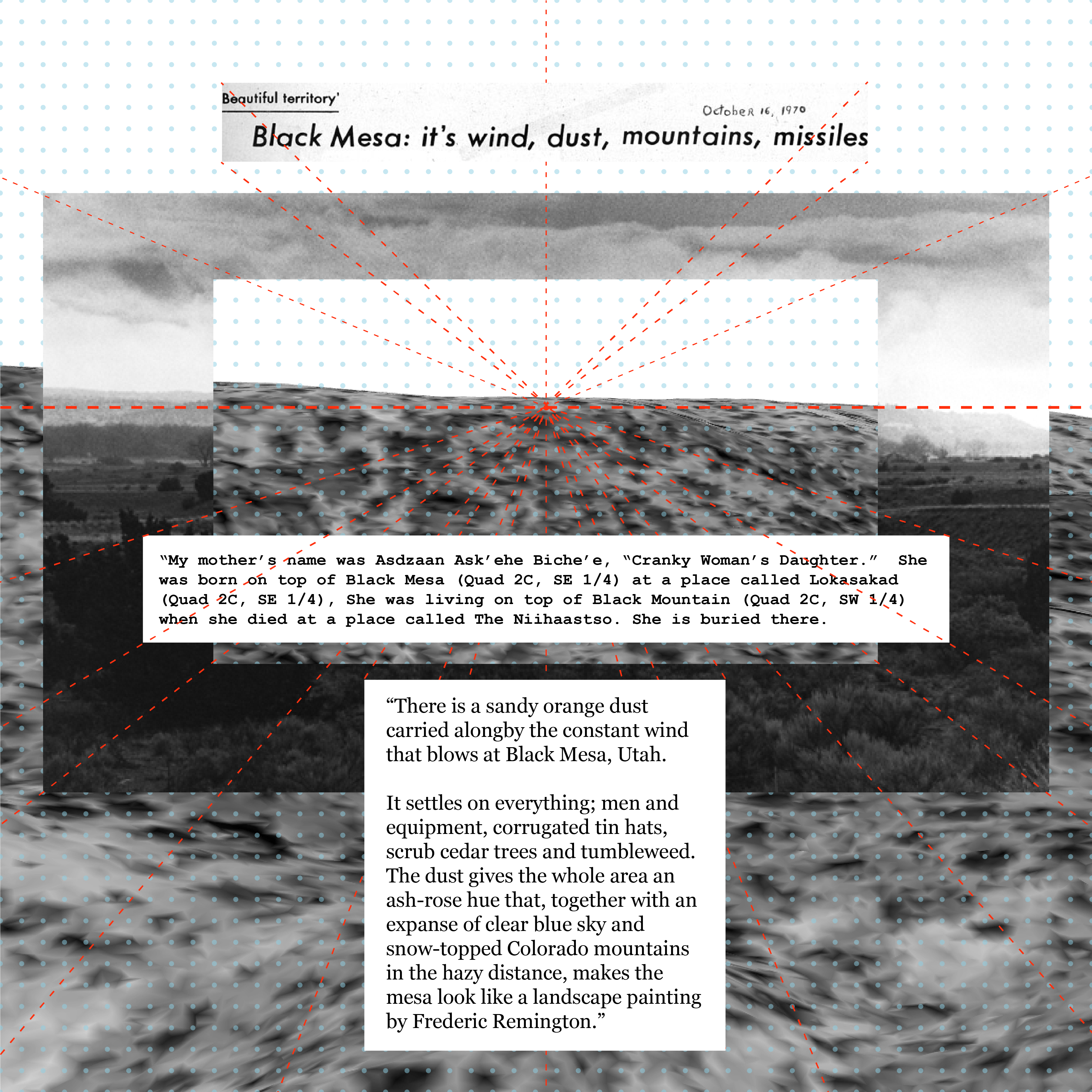

A0001 Doris Duke, 0473, Irene Shorty, Special Collections, J.Willard Marriott Library, The University of Utah

Sources:

A0001 Doris Duke, 0399, Albert L. Lyman (1968), Special Collections, J.Willard Marriott Library, The University of Utah

A0001 Doris Duke, 0473, Irene Shorty, Special Collections, J.Willard Marriott Library, The University of Utah

Sources:

A0001 Doris Duke, 0399, Albert L. Lyman (1968), Special Collections, J.Willard Marriott Library, The University of Utah

A0001 Doris Duke, 0473, Irene Shorty, Special Collections, J.Willard Marriott Library, The University of Utah

Sources:

A0001 Doris Duke, 0399, Albert L. Lyman (1968), Special Collections, J.Willard Marriott Library, The University of Utah

A0001 Doris Duke, 0473, Irene Shorty, Special Collections, J.Willard Marriott Library, The University of Utah

Sources:

A0001 Doris Duke, 0399, Albert L. Lyman (1968), Special Collections, J.Willard Marriott Library, The University of Utah

A0001 Doris Duke, 0473, Irene Shorty, Special Collections, J.Willard Marriott Library, The University of Utah